Transcript of keynote delivered at the 11th European Spring School of the Catalan Society for the History of Science and Technology, Llatzeret de Maó, Mehón, Menorca.

5 May, 2022.

Historians are experts on the past. Rarely are we asked to commentate on the future.

However, the pandemic of Covid-19 – and the crises it has precipitated – has seen a renewed interest in the history of medicine and the sort of expertise only professional historians can offer.

No doubt, like me, many of you can recall your own “Covid moment” when after years of anonymous toil in the archives your research suddenly became “relevant” to health policy makers and journalists beat a path to your door.

As someone who had published a book on the history of pandemics shortly before the emergence of the novel coronavirus, I have had many Covid moments in the last two and a half years.

Initially, the questions were the sort that should more properly have been addressed to a virologist or an epidemiologist. How concerned was I about the reports of an atypical pneumonia in Wuhan?

Did the fact that the coronavirus shared 96 percent of its genome with SARS, a virus that had caused a multi-country outbreak in 2002-2003, concern me?

Should we impose strict border controls and quarantines or was there a risk that such measures would impede the distribution of vital medical supplies and plunge the global economy into the worst depression since the 1930s?

These inquiries intensified with the lockdown of Wuhan and other cities in Hubei province, restricting the movements of 50 million people, and grew ever more anxious as the Chinese premier Xi Jinping ordered the construction of two new hospitals in expectation of an influx of patients with severe breathing difficulties.

Watching the astonishing video of bulldozers preparing the ground for what would become The Fire God Mountain and Demon God Mountain hospitals and the pictures of the emergency “waiting rooms” in Wuhan with rows and rows of empty cubicles awaiting patients, I was reminded of this iconic image taken in the Spring of 1918 at Camp Funston, a large US Army training camp in Kansas, where American recruits were being prepared for military action in northern France.

The picture shows hundreds of soldiers laid out on cots in an emergency influenza ward. The vast majority suffered a brief, three-day fever, but about a fifth of the 1,200 men who were hospitalized developed aggressive pneumonias, and 75 died, leading some historians to conclude that this may have been a herald wave of the so-called Spanish flu.

I found myself returning to this image again and again during the initial weeks of the coronavirus pandemic – and as my Twitter feed filled with images of desperate patients besieging emergency rooms in Wuhan, I could not help but wonder whether history was repeating itself.

It hasn’t of course – or not exactly.

Though to date some six million people have died of Covid-19 globally – 18 million using the measure of excess deaths – aproximately 50 million are estimated to have perished in the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic (equivalent to about 160 million in current population terms).

And though SARS-CoV-2, as the coronavirus is officially known, is roughly twice as infectious as the H1N1 Spanish flu, it has not turned out to be the “Big One” long predicted by Bill Gates and others.

If we are to believe the prophets of pandemic doom, that event lies in the future – in a period that some writers are already referring to as the “Pandemicene” – though whether it will be our future or our children’s no one can say.

However, it is fair to say that the measures taken to contain Covid have been exceptional. Never has social distancing been applied at such a scale, and never have so many people been locked down at the same time – or for so long.

To take just one example, the third British national lockdown lasted 194 days, more than three times the length of the quarantines imposed during the plague of Florence in 1630.

Because the pandemic has coincided with a period of rapid global communications and economic and political turmoil, it is tempting to see our experience as unique – hence the claim made by the New York Times’s columinst Thomas Friedman early on in the pandemic that Covid-19 was “our new historical divide” and that henceforth there would be “BC”, the time Before Corona, and “AC”, the time after After Corona.

However, following the war in Ukraine that periodisation looks questionable. As in 1918, when a war in Europe also overshadowed a pandemic, Covid-19 may turn out to be a footnote to a much bigger and more far-reaching global crisis.

Such statements remind us of the pitfalls of premature judgements and the danger of privileging present-day narratives over deeper genealogical analyses. Rather than looking to the past in search of historical “lessons”, medical historians need to be alert to discontinuities with the present and be wary of drawing shallow analogies that ignore the specific social, cultural and political contexts that shape the reception of disease in different historical periods.

For Erwin Ackerknecht, Henry Sigerist and the other founding fathers of our discipline, disease was both a biological entity and a phenomenon older than recorded history – one that could not be understood apart from its diverse clinical manifestations and medical and cultural framings.

Theirs was an approach which actively sought to integrate biology and public health practice with insights from geography and anthropology and which was not afraid to engage with longue durée perspectives.1 And it was an approach that emphasized the importance of social relations and the way that ideas of contagion and contamination have often been instrumentalized for political ends.

Taken up by Ackerknecht’s student, Charles Rosenberg, these ideas became foundational to the social history of medicine.

In his book, The Cholera Years, and his influential 1989 essay, “What is an Epidemic?”, Rosenberg – who was writing just as AIDs was beginning to challenge the hubristic assumption that medicine had solved the problem of infectious disease – explained how epidemics were not only biological phenomena but social “framing devices”.

Or, as he put it the The Cholera Years, epidemics are “ingeniously designed natural experiments” which allow historians to examine “fundamental aspects of society in a controlled and abundantly documented context”.

Rather than seeing disease in terms of contamination and as something that ought to be eradicated, he encouraged medical historians to study the complex ecological configurations and interrelationships between pathogens and human and non-human bodies. In this way, Rosenberg sought to break down facile yet durable typologies of purity and danger.

When sufficiently severe, he argued, epidemics also acted as societal stress tests, exposing religious, moral and political fault lines and drawing responses from every sector of society.

Taking inspiration from Camus’s allegorical novel La Peste, Rosenberg argued that epidemics followed a characteristic dramatic arc, from denial and disbelief to progressive revelation, followed by recrimination, blame and the search for scapegoats. The final act came with urgent demands for collective action, after which, as cases subsided, the epidemic would cease to command attention and slink into obscurity.

In this way, Rosenberg encouraged historians to pay attention to the similarities between epidemics and look for continuities with the past. At the same time, his framing approach provided historians with a way of comparing and contrasting epidemics across time and cultures by looking at variations in national and transnational responses, whether quarantines or enhanced surveillance, social distancing or fear and flight, cooperation or competition.

However, as Charteris and McKay point out in their recent Centaurus Spotlight article, while epidemics may be “captivating moments of drama, they are merely pinpoints in the historical record: the ... tips of icebergs… that too often distract from the powerful mass hidden beneath the surface”.

As well as attending to the dramaturgic form of epidemics, historians of medicine, science and technology need to be alert to the ways in which the mathematical and life sciences shape our current understandings of pandemics and their pathogens. These sciences – and the knowledge they lay claim to – are not “givens” but also have a history, one that medical historians and sociologists of science are well-placed reconstruct.

In what follows, I will briefly highlight some of key research questions thrown up by the coronavirus pandemic, before concluding with some reflections on what Covid-19 teaches us about medical history and its future direction of travel.

A good place to begin would be with some of the key terms employed in the epidemiological discourses around Covid and naively amplified by journalists and medical commentators unaware of their complex, and often contested, histories.

For instance, you may recall that at the beginning of the pandemic many scientific experts confidently predicted that the pandemic would end once we achieved a threshold known as “herd immunity”. This was the notion that when a sufficient number of people had been infected with Covid, they would be immune to re-infection and could not continue to transmit the virus to susceptible individuals.

Interestingly, this threshold was never defined. However, based on epidemiological modelling of the reproductive rate of the coronavirus, it was thought to kick in when 70 percent of the population had been infected and had recovered.

Since no Covid vaccines were available at the start of the pandemic, this led experts in the UK and elsewhere to advocate a policy of allowing the coronavirus to spread unimpeded through the population. As the U.K.’s chief scientific adviser, Patrick Vallance, put it the goal was to “build up some kind of herd immunity whilst protecting the most vulnerable”.

The alternative – we were led to believe – would be a series of stop-start lockdowns that would temporarily reduce the peak of the epidemic but leave the majority of the population susceptible to infection once the restrictions were lifted. The poster child for this policy was Sweden, a small Nordic country whose biggest city, Stockholm, is less densely populated than Oslo, and two thirds the size of London.

Nonetheless, such was the sway of the herd immunity concept that when the first Covid vaccines became available, it continued to dominate the exit strategies of countries in the Global North, hence Antony Fauci’s assertion that vaccinated individuals were “a dead-end for the virus” and that once populations reached “the threshold of herd immunity,” infections would “almost disappear”.

What Fauci and other prominent scientific experts failed to mention is that herd immunity is a concept borrowed from veterinary medicine and which was taken up by British epidemiologists in the aftermath of the 1918 flu pandemic.

Through experiments on caged mice, British epidemiologists like Major Greenwood and his colleagues at the Medical Research Council attempted to understand how the shifting ratio of susceptible and immune individuals fuelled or restrained epidemics.

Their central hypothesis was that epidemic waves “fall because the average resistance of the herd is raised”. But this did not mean that a pathogen disappeared from a population. “Another wave will follow it at a later date,” they continued, when waning immunity causes “the average herd immunity to fall below some critical level.”

In other words, as David Robertson has argued, herd immunity was not so much an elimination threshold as “a mechanism for epidemic abatement”. In the 1920s and 1930s it became a staple concept for epidemiologists interested in disease ecology, helping to articulate the population dynamics of diseases such as diphtheria and influenza.

It was following the Second World War – and the production of sterilizing vaccines against polio, and later, measles – that it came to signal the point at which mass vaccination would halt the onward transmission of disease.

Now it is evident that, as with influenza, vaccination against Covid does not produce sterilizing immunity, we can see that – stripped of its history – this concept of herd immunity was misleading and unhelpful.

Misleading because the Elysian fields of herd immunity were – and perhaps never will be – reached. Unhelpful because it led some to countenance a policy of “letting the virus rip” or to advocate unworkable policies such as the Great Barrington Declaration.

The distinction between pandemic, epidemic and endemic is similarly arbitrary.

As Jacob Steere-Williams has argued, the notion of endemicity can be traced to attempts by colonial-era epidemiologists to characterise diseases such as cholera, malaria and plague as endemic to Asia and other outposts of the British Empire.

With the rise of germ theory in the 1880s, however, the notion of an endemic disease subtly changed to mean a disease that was always present in a given location but which could erupt into an epidemic or a pandemic at any time due to ecological, environmental factors and/or social factors – or a combination of all three.

The irony is that this notion of endemicity is now being deployed by populist politicians keen to call time on the pandemic and distinguish their polities from those of countries such as China and Hong Kong, where, due to sub-standard vaccines and high levels of vaccine hesitancy, Covid continues to present a high risk of hospitalization and death, resulting in a “zero-Covid strategy” and continued restrictions on people’s freedom of movement.

It also glosses over the fact that each day thousands of people in sub-Saharan Africa continue to die of tropical diseases, such as malaria, that were once endemic to Europe and the southern United States. But, of course, such diseases are no longer considered a problem for the Global North because they are no longer “pandemic”.

Another term that may repay investigation is “variants of concern”. Covid-19 has been described as the first pandemic of the “post-genomic” era. Certainly, the sequencing of mutations in SARS-CoV-2, to give the novel coronavirus its official designation, has been unprecedented, hence the WHO’s alphabet soup of variants from Alpha, through Delta and Omicron.

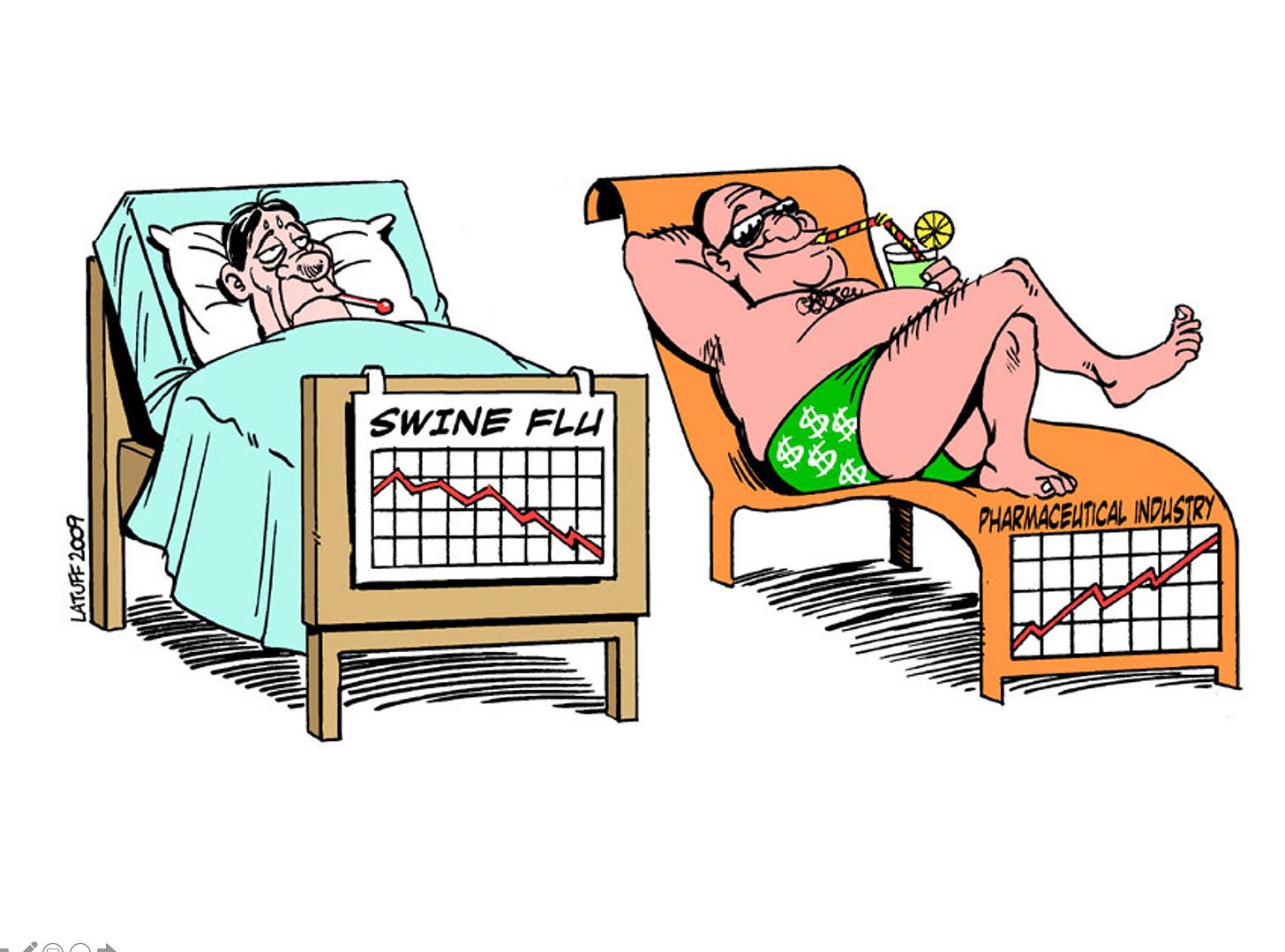

But genomic technologies also played a critical role in the WHO’s decision to trigger a global pandemic alert in 2009 following the sequencing of the H1N1 swine flu that emerged unexpectedly in Mexico and its identification as a novel recombinant virus.

However, when the swine flu turned out to be no more severe than a regular seasonal influenza, the WHO’s decision fuelled conspiracy theories about pharmaceutical profiteering, eroding trust in science and contributing to the spread of vaccine hesitancy.

We need better histories of these genomic technologies and their integration into health surveillance systems that are designed to forewarn us against so-called “spill-over” events from animal reservoirs. In particular, we need to interrogate how these technologies produce discourses around “emerging infectious diseases” and other supposed biosecurity risks.

It is at times like these that historians of science and medicine can perform a useful public service by opening-up the black box of “taken-for-granted” scientific terms and reconstructing their history.

Most of all, we need to interrogate what it might mean to “follow the science” when the science itself is uncertain and hard data is wanting, as was the case at the beginning of the pandemic when the role of asymptomatic spreaders and Covid’s infection fatality rate was unclear. At such times, we are returned to what the historian of science Lorraine Daston calls “a state of ground-zero empiricism” reminiscent of the scientific debates of the seventeenth century when, as she puts it, “everything was up for grabs”.

Until now, I have been speaking mostly of discontinuities. But medical historians also need to be alive to continuities with the past.

Those images of coronavirus “waiting rooms” in Wuhan should have reminded us of the picture of the emergency influenza ward at Camp Funston in 1918.

When face masks began appearing on the streets of China, Hong Kong and Seoul, we should have recalled that the use of face masks to block the transmission of airborne pathogens date back to the pneumonic plague outbreak in Manchuria in 1910, and that in 1918 several US cities also mandated face masks in shared public spaces.

Moreover, while the scale of today’s lockdowns is unprecedented, quarantines are a tried-and-tested response to outbreaks, one that has changed little since 1377 when Dubrovnik banned travellers from plague-infested areas entering the city.

Whether they take the form of a lazaretto, as in seventeenth century Ancona or here in Mahon – or a biohazard tent – their spatial logic is straightforward and easily understood. Indeed, Alison Bashford argues that “there are very few medical practices that cast back and forward in time with such full and easy comprehensibility”.

At the same time, we need to recognise the layers of uncertainty in traditional historical accounts of epidemics and people’s supposed behavioural responses to them. For instance, I have lost count of the number of times that journalists have cited the village of Eyam as an early example of spontaneous community shielding.

According to traditional accounts, in 1666 the Eyamites shut themselves off from the outside world in order to prevent plague spreading to the neighbouring parish in Derbyshire, in the north of England. Their self-sacrifice is said to have resulted in the deaths of 265 villagers.

Three modern musicals, alongside numerous poems, children's stories, and plays have cemented this British account of Eyam’s heroism. Yet Patrick Wallis has demonstrated that little is “stable or definite in the story of Eyam's plague.”

In the later seventeenth century, few commented on this supposedly exceptional event. Instead, it was in later periods – especially in the nineteenth century, when fears of cholera sparked a “wider literary and historical fascination with past epidemics”– that writers and historians shaped a version of what happened in Eyam in 1666.

In other words, the story of Eyam is most likely apocryphal. If the role of history really is to teach us lessons, then the lesson of Eyam is that we continually rewrite the history of disease in light of our current preoccupations.

The task for scholars then is to cultivate a more profound imaginative engagement with the history of pandemics, one that is wary of overly presentist narratives but which is also not afraid to ask big questions about the limits of scientific expertise and our interactions with microbes over longue durée time frames.

To succeed, I believe, such an approach demands an active dialogue between the life sciences and the medical and environmental humanities. In particular, it requires medical historians interested in the genesis of pandemics to cultivate exchanges with evolutionary biologists and molecular pathologists and to be alive to the ways in which pathogens serve as what Monica Greene calls “tracer element(s)” and “living chain(s) of evidence that can tie together vastly distant times and places.”

And it requires us to resist reductionist disease models and the reification of science at the expense of tried-and-tested public health interventions and hard clinical realities.

In short, we need to foster a more capacious pandemic imagination. For it is only by asking questions about how the past develops over centuries and millennia – and how people coped during previous times of plague - that we can begin to address the issue of our survival and flourishing in the present.2

Even now, hardly a day goes by without some announcement about the basic reproductive number of the virus. But as useful as this epidemiological measure may be for plotting the rate of increase of the virus and “flattening the curve”, it does not tell us when or how we will be delivered from our pandemic purgatory, much less what we need to do to prevent disaster from recurring and build a better world for our children.

As the WHO’s Director General remarked in June 2020, six months into the coronavirus pandemic: “None of us could have imagined how our world – and our lives – would be thrown into turmoil by this new virus.”

We cannot allow our imaginations to fail us so catastrophically again.

The term longue durée was coined by Fernand Braudel and employed by members of the French Annales school to denote a perspective on history that extends further into the past than both human memory and the archaeological record. Here, I use it both in its original sense of a history measued in millennia and also to denote an approach to history that is actively engaged with what David Armitage and Jo Guldi call “the knowledge production that characterizes our own moment of crisis”. Armitage, D. and Guldi, J. “The Return of the Longue Durée An Anglo-American Perspective”, Annales HSS, 70, no. 2 (April-June 2015): 219–247.

For a defence of histories concerned with human flourishing in the present see David Armitage “In Defence of Presentism” forthcoming in Darrin M. McMahon, ed., History and Human Flourishing (Oxford, 2022).