“They gave her a bed to die in”

From the delay in locking down to the failure to prepare for large patient surges, evidence to the UK Covid inquiry this week suggests the pandemic was not just a scientific failure but a moral one.

I owe Baroness Heather Hallett an apology. When the chair of the UK’s inquiry into Covid-19 began inviting witnesses to give evidence two years ago, I criticised her for seeming to overrule direct testimony from the bereaved. “We will not consider in detail individual cases of harm or death,” a spokesperson for the inquiry told me.

At the time, my concern was that unless the inquiry was to hear directly from those who had seen their loved ones perish from Covid for wont of sufficient critical care beds – or due to opaque clinical decisions - the inquiry would not be in a position to unwrap thorny ethical questions to do with the issuing of Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Notices (DNARs) and the value that we, as a society, put on the preservation of life, especially the lives of clinically vulnerable people.

These issues were summed up for me early on in the pandemic by a question that Boris Johnson’s special advisor Dominic Cummings scribbled on a Downing Street whiteboard on 13 March 2020: “Who do we not save?”

As we now know from Hallett’s module 1 report into the UK’s preparedness and resilience for a pandemic, the reason Cummings was forced to pose that question was because – incredible as it may seem now – the UK had no plan to suppress a pandemic that might result, as Covid did, in 230,000 deaths, let alone one that might cause 837,000 excess deaths, the figure anticipated in the worst-case planning scenario based on pandemic influenza. It was only once it became clear that coronavirus cases were doubling every two to three days and that the nation’s supply of critical care beds and ventilators was likely to be overwhelmed by a surge in severely ill patients, that Whitehall belatedly leapt into action.

As Cummings explained in his witness statement to the inquiry, the reason he had put the question so starkly was that he felt it was only by doing so that he could seize the attention of Johnson and the experts who advised him.

I was forcing people to consider, ‘On whom are our errors going to fall worst, who is not going to be saved in this disaster, and if forced to choose because of NHS collapse how does the system do this (e.g prioritise mothers of small children)? Because only by facing such awful questions could we have a chance to change the plan fast…

The sort of person Cummings might have had in mind was Susan Sullivan, a 56-year-old woman with Down’s Syndrome who died at Barnet Hospital on 28 March 2020 after being denied access to intensive care because of her disability and what a medical registrar had termed “cardiac comorbidities” (a reference to a condition known as “mitral and aortic regurgitation” that in Susan’s case was regulated by a cardiac pacemaker). It was precisely because of my concern that it was vital for Hallett to hear directly from Susan’s parents, John and Ida, in order to get to the bottom of how such decisions had been made – and on what authority – that I pressed her not to relegate their testimony to a parallel process.

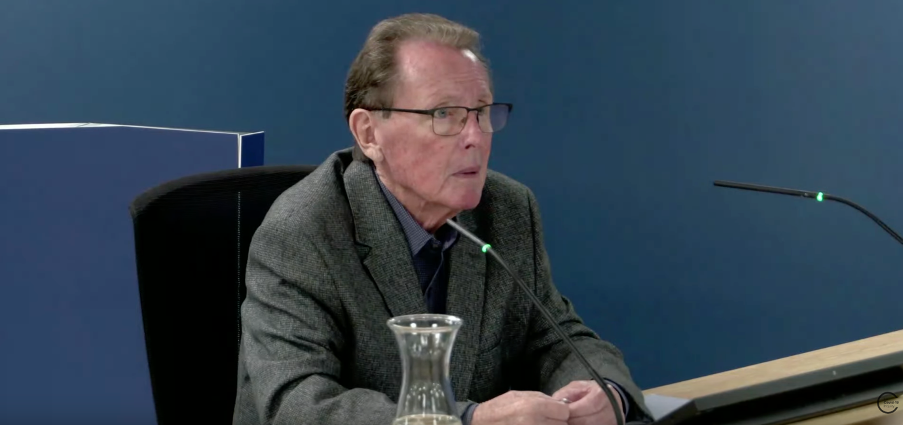

Hallett was as good as her word and at the start of module three, which is examing the impact of the pandemic on health systems, she called John Sullivan to the stand. You can listen to his testimony here.

In documents highlighted by Jacqueline Carey, lead counsel to the inquiry, an investigation by the Royal Free Hospital Trust on behalf of Barnet hospital acknowledged that neither Down’s Syndrome nor the presence of a cardiac pacemaker constituted “exclusion factors for ITU on their own”. The inquiry also heard how doctors had deemed Susan “not for resuscitation” despite Ida’s express wishes that her daughter should be resuscitated should the need arise.

As John told Hallett: “They gave her a bed to die in because she had Down’s Syndrome – end of.”

What makes Susan Sullivan’s case so important is that her death came at exactly the time when England’s Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty, and other senior scientific advisors were doing an about turn and scrambling to prepare the NHS for a surge in patients that could overwhelm the UK’s critical care capacity and send tens of thousands of people to premature deaths. This sudden change of gear from what Cummings calleda “Plan A” – basically, no mitigation and allowing the virus to spread umimpeded – to “Plan B” – adopting lockdowns and other control measures to prevent the NHS collapsing – got underway in the second week of March.

However, it was only on 20 March – three days before the first national lockdown and seven days before Susan was admitted to Barnet hospital - that Whitty convened a panel of expert ethicists in Whitehall to consider something that, in retrospect, he should have been thinking about from the start: namely, if, in the event, there were insufficient resources to treat everyone who required critical care, which patients should be prioritised and which should not? Or as the philosopher and biopolitical thinker Michel Foucault might have put: “Who should we make live, and who should we let die?

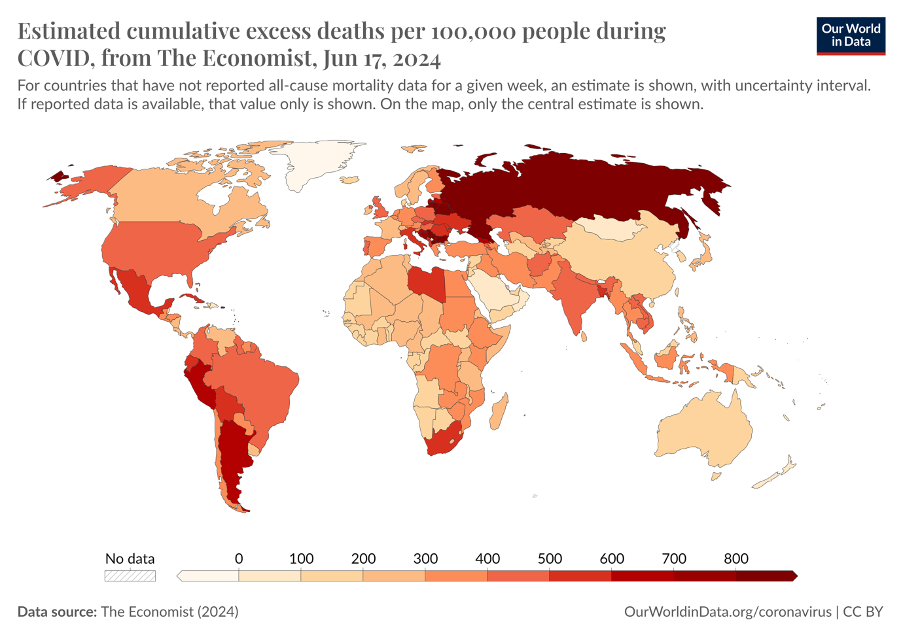

I have dwelt at some length on this question, and the background to it, because it goes to the heart of everything that followed. For it was due, in part, to the strategic flaws in what passed for pandemic planning pre-Covid, and the failure to consider the ethics of allowing a new virus with an unknown case fatality rate to spread freely through an unvaccinated population, that the UK suffered the highest excess mortality rate of any western European country, except for Italy and Spain. This was not only a generational scientific failure, as the editor of The Lancet Richard Horton has argued, but a moral one.

In particular, senior Whitehall officials and scientific advisors failed to put ethical considerations and societal values front and centre of the UK’s pandemic response, resulting in clinically vulnerable people - or those whose age or disabilities singled them out as less likely to survive Covid - receiving a lower standard of medical care. Exactly how these individuals were denied access to critical care units – and on whose authority - is one of the biggest unanswered questions of the pandemic.

We know that on 20 March 2020, Whitty asked the Moral and Ethical Advisory Group to come up come up with a population-wide frailty scoring system for rationing access to ventilators and other resources that were likely to be in high demand in the event of a pandemic surge. However, on 28 March – in other words, the same day that Susan Sullivan died having been denied access to Barnet’s ITU – Whitty disbanded the group, having decided the NHS had sufficient resources to cope with a run on critical care beds and that such decisions were better left to frontline physicians using a clinical frailty scale scoring system approved by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). You can read more about this frailty scale in my previous post on the Sullivan case.

Clinically Vulnerable Families (CVF), a voluntary organisation representing individuals who were required to shelter because of pre-existing medical conditions, suspect the scale was used to impose DNARs on individuals who were deemed unlikely to benefit from intensive care or to survive resuscitation. Indeed, CVF has documented hundreds of cases where DNARs were apparently placed on people’s records without prior discussion with them or their family’s consent. And this week Jonathan Wyllie, the former president of Resuscitation Council UK, said he knew of at least one trust that had issued a blanket "do-not-resuscitate" notice across its units.

If so, this would breach NHS England guidance. NHS England has always insisted that blanket DNARs are unlawful and Stephen Powis, the NHS national medical director, says he “repeatedly instructed staff that no patient who could benefit from treatment should be denied it”. But, thanks to Lady Hallett, we now know this didn’t happen in the case of Susan Sullivan and, possibly, in the cases of hundreds of other patients too.

Just as important, however, is what the latest revelations tell us about how the failure to plan for a pandemic that could overwhelm the NHS led senior advisors and officials to buck their responsibility for population triage and the allocation of health resources along rational lines. Instead, the burden for making these life-and-death decisions was placed on hospital trusts and frontline physicians.

In retrospect, that may have been the biggest failure of all.