Some said it came from the East, as pandemics usually do. Others, from Khan Younis where the corpses of babies lay rotting under rubble and ash damp with mothers’ tears. In fact, the source of the contagion was Africa, a continent where war and hunger is never far from the door.

The fighting that year had been particularly fierce in Southern Sudan, sparking a famine that drove millions of refugees to seek refuge in northern Uganda. There, they were greeted by officials from the World Food Programme (WFP), or what was left of it following the cuts to international aid that followed Trump’s disastrous tariff war. The cuts had decimated WFP’s stocks of maize and pearl millet, but fortunately there just enough sorghum to go round. However, there had been no time to construct storage sheds to keep the sorghum dry. Instead, officials had stacked the sacks of sorghum one upon the other in the open, where they could not help but be exposed to rain and dew.

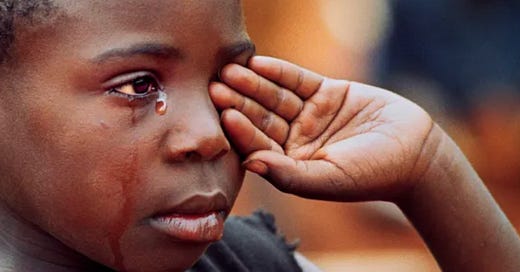

When the refugees spied the towering stacks of sorghum they thought it was an apparition. Some of the sorghum had turned mouldy but it was better than the roots and leaves they had devoured on the river banks teeming with black fly on the trek from Sudan and they fell on the food as if it was a gift from the gods, their eyes welling with tears. Afterwards, their stomachs swollen with gratitude, the refugees fell into exhausted stupors, dreaming of absent loved ones and their abandoned villages and farms.

The following morning, their hunger was keen as ever, so they filled their stomachs again, and again. By the week’s end, the sorghum was gone, but now the refugees had a new problem – the children were sobbing. Whether it was the unfamiliar feeling of fullness or the realisation that the world cared little for their plight and they would likely never return to their homes, no one could say, but the sobbing went on late into the night, and the next morning several children suffered epileptic fits. When their parents asked what was wrong, they were unable to answer. Nor did they have the energy to attend the makeshift school WFP staff had erected beside the sorghum. Then, one by one, the children started nodding and weeping uncontrollably. As their tears fell on the parched earth mixing with the spores from the rotting sorghum, they were lifted into the air by a sudden breeze from the southwest. The breeze carried the tears all the way to Ghana, at which point they were lifted even higher into the atmosphere by a harmattan from the Sahel. As the refugees’ tears mixed with pollen, and sand from the desert, the sky turned hazy and dark. Then, at the Gulf of Guinea, the particles began to drift across the Atlantic.

Going Viral is a reader-supported publication. If you would like to read more articles like this please consider subscribing to my Substack.

On Good Friday, a baker in the Marais noticed a fine dust on the pavement in front of his shop and a smell like burnt almonds. Had he left some pastry out overnight by mistake? Then he remembered, he was closed for the long holiday weekend and he had shut his oven down. The odour reminded him of his father, a hero of the resistance who everyone agreed had made the best madeleines in Paris and who had died far too young. In an instant his eyes welled with hot, salty tears and he also began nodding and weeping uncontrollably. The crying went on all day and into the evening, until exhausted, he fell into a deep and uneasy slumber. The next day he awoke with a headache and a raging thirst. Then came more tears and a peculiar buzzing in the ears.

On Easter Sunday, in what would be his final public appearance, Pope Francis appeared on the balcony of the Vatican to reassure the anxious crowds gathered in St Peter’s Square:

“Sisters and brothers, especially those of you experiencing pain and sorrow, your silent cry has been heard and your tears have been counted… Not one of them has been lost!”

Francis’s words resonated not only with Catholics but with people of all faiths. Some speculated the tears were a reaction to the genocide in Gaza and the incessant shelling of Kyiv; others, a response to the famine in Sudan and the Horn of Africa or an acute form of eco-grief.

People cried for small things, and for big things; they cried for that time they forgot to feed their pet goldfish; and for the desperate refugees stranded in the Mediterranean; at soppy pop songs and their elderly mother who could no longer recall their birthday. But most of all they cried for their lost innocence and helplessness.

At first, the right-wing press dismissed the “blubbering”, blaming it on “the woke mind virus”. The government, fearing social meltdown, urged people to show more “grit”. “Whatever happened to the stiff-upper lip?”, asked a backbencher from the shires. But as trains ground to a halt and one by one offices shuttered, it became clear that this was no ordinary affliction and the sobbing no ordinary pathology.

The epidemic was worst of all in Japan, where people trained to believe that crying was shameful and a sign of weakness, began bandaging their eyes in public. But the bandages soon grew wet and heavy and, unable to stem the torrents, people began nodding even harder in the hope of shaking the tears from their heads, for where else could they be coming from? But the well ran deep and all it took was the sight of a fellow weeper to open the floodgates.

Come September the medical press was full of accounts of “inconsolables” and speculation that, despite the glorious weather, it was an unusual form of Seasonal Affective Disorder; others, that the tears were a type of emotional contagion. Doctors were inundated with requests for Paxil and Prozac; sales of MDMA spiked on the Dark Web. The hashtag “mindfulness” trended on Tiktok.

“It was sad,” everybody agreed, “to see so many sad people”.

“It was sad,” everybody agreed, “to see so many sad people.” At which point, the World Health Organization was forced to name the disease. SAD was already taken so they simply added another S for “severe”.

The SSADs epidemic continued into 2026 and beyond. Then, on a wan day in mid-winter, something remarkable happened: people stopped cradling their heads in their hands and, for the first time in months, looked up. Not in the way they had in the “before times”, when another person’s tears were a source of embarassment and unease, but with vision sharpened by a surfeit of salt, electrolytes and proteins. That’s when people realised that no one had a monopoly on tears and that each was part of a great river that cut across national, religious and ethnic divides, bringing hope to broken hearts.

Lyrics that the day before had sparked waves of involuntary gushing suddenly took on new meaning and, when people paused to take a breath, they began giving them their full attention. A song by an obscure London-based klezmer band containing the line, “Every tear in your eye is s a drop in my mind”, struck a particularly empathetic chord and was taken up as an anthem. But perhaps the phrase that best caught the new public mood was the Billy Bragg song about the Four Tops singer Levi Stubbs, with its refrain, “When the world falls apart, some things stay the same”.

Yes, the world was falling apart; yes, images of bloodshed, hunger, fires, and famines continued to fill peoples’ screens. But for better or worse it was their world, and in the new republic of tears forged by the mouldy sorghum they were all in it together.

*****

A note on the sources that inspired this story:

Nodding syndrome (NS) is a neurologic disorder of children with typical onset between the ages of 5-15. First identified in Tanzania in the 1960s, NS is characterized by head dropping movements, cognitive impairment and seizures. One of the best-documented outbreaks occurred in Kitgum, in northern Uganda, in 1998 during an internal armed conflict that displaced thousands of children into camps. Afflicted children have trouble concentrating in school and tend to be shunned by their peers, resulting in depression and sadness.

In 2001–2002, during an outbreak in Southern Sudan, experts from the World Health Organization noted a strong association with the ingestion of red sorghum delivered by the World Food Programme. It is hypothesized that the practice of storing sorghum in outdoor stacks encourages the build-up of moisture, promoting the growth of mycotoxins (toxic fungi). Other suspected causal agents include prior infection with measles, a parasite transmitted by blackflies, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The quote from Pope Francis is from his final public appearance on Easter Sunday in St Peter's Square.

In Japan, crying tends to be regarded as a sign of weakness. In recent years, “crying cafes” have sprung up in Tokyo and other cities to address the stigma and persuade people that crying regularly can be a good way of relieving stress.

The lyric “Every tear in your eye is s a drop in my mind” is taken from the song Every Time by Oi Va Voi, a British folk klezmer-fusion band.

The lyric “When the world falls apart, some things stay the same” is from the song Levi Stubbs’ Tears on Billy Bragg’s 1986 album, ‘Talking With the Taxman About Poetry’.

Further reading:

Michael S. Pollanen, et.al., Nodding syndrome in Uganda is a tauopathy. Acta Neuropathology, 136, 5 (2018 ):691-697.

WHO East Mediterranean Region, Determining current levels of mycotoxin contamination in Sudanese sorghum.

Florence Miettaux, The fight to cure South Sudan’s mysterious neurological disorder. The Guardian, 25 March, 2024.

Mark Honigsbaum, Read it and Weep: why regular crying is cathartic. The Observer, 24 May 2025.

Going Viral is a reader-supported publication. If you would like to read more articles like this please consider subscribing to my Substack.