The Next Pandemic? A Scenario.

It began with a chimpanzee-trekking tour of a remote forest in Uganda and ended with the outbreak of a deadly new disease. And all because of health cuts and the disruption of a wild animal habitat.

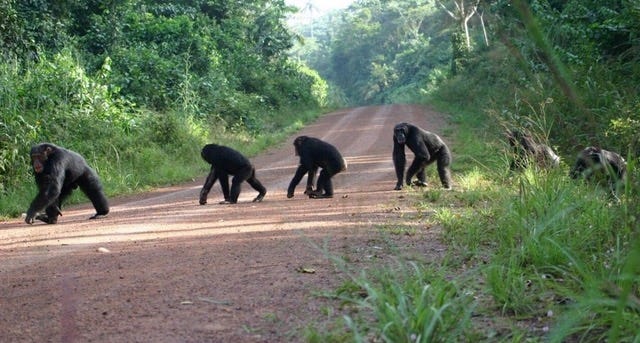

Deep in the Budongo Forest on the shores of Lake Albertine in western Uganda, a group of zoology students from Montreal are on the trip of a lifetime. Together with tourists from the United States and France, they have come to study chimpanzees in their natural habitat.

A sanctuary for nature lovers, the Budongo Conservation Reserve spans 825km2 and is home to 600 chimpanzees, including the Sonso and Waibira communities. Roaming the area between Budongo Forest and Murchison Falls National Park, most of the chimps are habituated to humans and after a two-to four-hour trek they can be observed at close quarters playing, feeding and napping. More adventurous tour groups can venture deeper into the reserve where they may spy chimps un-used to humans and gain a deeper understanding of their routines.

On this day in late May, the tour party stumbles on a family of chimps gathered around a tree hollow. Unlike other chimps they have observed, these are slow and listless and make no attempt to run away. Instead, one by one they reach their hands into the hollow and scoop decaying organic matter into their mouths. Chimps in the Budongo reserve have been known to eat earth in search of minerals and chemicals missing from their diets, but the guide has never observed this activity and motions for the party to move in for a closer look. The organic matter smells strongly of urine, and peering into the tree, the guide sees bats roosting in the hollow.

That evening he reports his finding to the Conservation Field Station and the following day forest rangers visit the tree hollow and set up cameras to capture the chimps’ behaviour. Every day they observe the chimps and other forest animals, such as black-and-white colobus and red duiker, visiting the hollow and feeding on the bat guano. Baffled by their behaviour, they report their findings to the Uganda Wildlife Authority who pass on the information to the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland.

Meanwhile, fuelled by the guano, the chimps regain their vigour and muscle tone and are soon swinging freely from trees. But a week later, two develop hiccups and begin vomiting and expelling explosive diarrhoea. When a ranger comes across one of the chimps apparently comatose on the forest floor he brings it to the field station for examination. There, a vet treats the chimp and takes faecal samples to check for parasites. But the tests come up negative and two days later the chimp dies.

Normally, autopsy samples would be sent to a nearby lab for analysis but cuts to USAID programmes have hit this region of Uganda hard. Instead, the samples, together with the guano, are dispatched to the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) in Kampala, 200km away. There, tests show the guano contains sodium and natural fertilisers such as nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium. But when scientists run a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) test there is a surprise. The guano also contains a novel coronavirus and several other viruses, some unknown to science.

By now the ranger has a sore throat and a splitting headache. When he vomits, he is rushed to the former colonial hospital in Masindi where it is assumed he has malaria and given intravenous quinine. But the next morning he is doubled-up in pain, with blood leaking from his eyeballs and that afternoon he dies. The autopsy reveals he has suffered massive internal haemorrhaging, leading medics to suspect a filovirus, such as Sudan Virus Disease (SVD), a species of Ebola that has caused previous outbreaks in Uganda.

Meanwhile, the students and tourists have checked out of their eco lodge in the Bodungo reserve and are speeding to Kampala. Their destination? Entebbe International airport, from where they will catch a direct flight to Doha in Qatar. At Doha, some will transfer to planes bound for Dubai, Paris, Washington and Montreal.

The virus – whatever it is – is about to go global.

By the time scientists at UVRI realise the danger, it is too late. En route to Doha, several tourists begin complaining of headaches and nausea and as they exit the plane to collect their baggage some begin to vomit. Others rush to the toilet with violent stomach cramps. A few of the Canadian zoology students and tourists, meanwhile, have dull headaches and pop Tylenol before boarding onward flights to Montreal and Washington DC.

The following day the Infectious Diseases Department at Makere University, in Kampala, issues an alert on PROMED (Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases), a surveillance system that monitors unusual disease outbreaks around the world. Twelve people in Masini have been hospitalized with suspected filovirus infections and two check-in staff at Entebbe airport are also reported to be ill.

The alert is picked up by scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. They immediately email UVRI to send them the filovirus sequence so they can type it and prepare countermeasures. But in Washington DC, the health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr has just ordered a US Army facility specializing in high-consequence pathogens to cease experimental work and the Department of Homeland Security has placed padlocks on all its freezers. Normally, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would send its elite Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) to Uganda to investigate. But EIS has been reduced to a skeleton service by the new administration and instead a CDC official who used to work for Kennedy’s Childrens’ Health Defence anti-vax group issues a statement blaming a contaminated batch of yellow fever vaccine and saying there’s “no cause for panic”.

Kennedy is wrong. Bundongo Virus Disease (BVD) turns out to be caused by a new strain of Marburg and a virologist’s worst nightmare. Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) was first identified in 1967 during simultaneous outbreaks in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and was linked to laboratory work involving African green monkeys imported from Uganda. Previous outbreaks in Uganda and Rwanda have proven deadly, with some outbreaks having a case fatality rate of 80 percent.

Prior to the election of Donald Trump, the Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington DC had been planning phase II trials of a candidate Marburg vaccine with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). But Kennedy is considering rebranding BARDA the “Office of Healthy Futures” and ending what he considers its “dangerous biowarfare experiments”. As a result, the US has no licensed vaccine or anti-viral treatment for Marburg.

Alerted by PROMED and suspecting the worst, Canada’s new Prime Minister, Mark Carney, orders all travellers from Africa, the Middle East and US to be detained at the border for medical examination. Not so the United States, however, where Trump issues a post on Truth Social giving Carney 24 hours to rescind his order against “American patriots”.

As the virus spreads from Washington DC to Philadelphia and Cleveland, there is panic buying of surgical gloves, masks and disinfectant. However, due to Trump’s trade war with China, the items are in short supply and the shelves of Walgreens are soon empty. Although the virus has a two-to-ten-day latency period, the symptoms are difficult to miss and people quickly learn to keep a distance from anyone showing signs of hiccups and/or nausea. Bars and restaurants spontaneously close their bathrooms and space tables a metre apart. Nonetheless, because of cuts to the National Institutes of Health and the administration’s failure to detain the arrivals from Uganda, 987 Americans perish in the outbreak before it is brought under control. By contrast, Canada suffers just one death, a young zoology student.

A pandemic has been averted – but only just. Had the chimpanzees been infected with a new strain of SARS, rather than Marburg, the world may not have been so lucky.

The scenario - its scientific basis.

The above scenario, though based in fact, is imaginary. For dramatic purposes I have made the infection in chimps obvious. In fact, most emerging infectious diseases [EIDs] from novel zoonotic agents tend not to produce clinical signs in their reservoir or intermediate hosts. If that had been the case, no one would have noticed that the chimps were infected and it would have taken far longer to type the filovirus and issue an alert.

Whether the next pandemic will be triggered by Marburg or some other virus on CEPI’s pathogen priority list, no one can say. Nor can anyone say at what point the H5N1 bird flu virus, which has been spreading unchecked in poultry and cattle in the US since March 2024 and has shown worrying adaptions to the human respiratory tract, will spark a major human outbreak.

But whether from bird flu or some other pathogen, another pandemic is a certainty – and like Bodungo Virus Disease, the trigger will most likely begin with a disturbance to a wild animal habitat.

Prior to the outbreak, chimps in the Budongo Reserve had never been observed eating bat guano before. But a few months earlier, local tobacco farmers had felled a large stand of shuttlecock palms to make curing strings for their tobacco leaves. In the process, they unwittingly eliminated the chimps’ main source of sodium, vital for maintaining fluid balance and nerve and muscle function. Without sufficient sodium, the chimps lose their appetites and become nauseous and disoriented. To satisfy their craving for sodium, they begin consuming bat guano instead.

In a recent study in Nature, scientists from University of Wisconsin-Madison filmed chimpanzees, black-and-white colobus (Colobus guereza occidentalis), and red duiker (Cephalophus natalensis) repeatedly consuming guano from the hollow of a tree in the Bodungo Forest Reserve.

In all, the researchers recorded 92 separate instances of guano consumption by the chimpanzees on 71 different days. The chimps either removed and ate the guano with their hands or drank adjacent water contaminated with guano using a leaf sponge. Analysis of the guano, deposited by Noack’s roundleaf bats (Hipposideros ruber), revealed 27 known viruses, including a betacoronavirus related to SARS-COV-2, and seven unclassified viruses from 12 families. These included parvoviruses, which cause respiratory disease; picobirnaviridae that cause diarrhea; and Iflaviridae, which are highly pathogenic to honeybees and their silkworm hosts.

In my scenario I added filoviruses to the viruses detected in the bat guano. In 2007, miners working in Kitaka Cave, Uganda, contracted Marburg following exposure to Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). Since then, Uganda has seen several other outbreaks of Marburg and Ebola, though whether this is due to better surveillance or a change in the incidence of spillovers is impossible to say.

Outbreaks of Marburg and Ebola have also been documented in Sudan, Kenya, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (see map below), and earlier this year 14 people in Kampala were infected with SVD and four died. There have also been recent outbreaks of Marburg in Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea. But the largest was in Rwanda where last year Marburg resulted in 66 cases and 15 deaths. The toll would have been higher but for the rapid deployment of the Sabin Vaccine Institute’s emergency vaccine, which reduced the case fatality rate to 22 percent, the lowest ever recorded for the disease.

Following that outbreak, the Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC) shared serum from recovered patients with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) in an attempt to identify key immune markers that could provide insights for vaccine development. Funding from CEPI will also strengthen Rwanda’s research infrastructure, enhancing its capacity to respond more effectively to future outbreaks. This sort of arrangement is a win-win as it enables countries at the forefront of EIDs to reap the benefits of vaccine research, thereby strengthening the surveillance of pathogens with pandemic potential and making the world collectively safer.

The good news is that under a new pandemic treaty recently agreed by the World Health Organization (WHO), countries have agreed to grant pharmaceutical companies access to pathogen samples and genomic sequences in return for the more-equitable sharing of drugs, vaccines and diagnostics. Manufacturers participating in the agreement must make 20 percent of the products available to the WHO during a pandemic – something that did not happen during Covid-19 and which resulted in inequities in the distribution of vaccines between rich and poor countries. However, the treaty does not include the United States, which withdrew from the WHO in February on Trump’s orders, depriving the organisation of around one fifth of its funding.

We know that 70 percent of all emerging and re-emerging diseases, including SARS, Ebola, Marburg and, almost certainly, Covid-19, have zoonotic origins. Yet, the White House recently endorsed the Covid lab-leak theory, undermining trust in mainstream science and the growing consensus that SARS-CoV-2 almost certainly emerged from a natural reservoir – most likely a bat in a cave in southern China or Laos – before being amplified by the wild animal trade. Better surveillance of the caves where bats exchange SARS and other high-consequence viruses – and better regulation of animal farms and the wild animal trade – could help reduce zoonotic spillovers. However, under Trump, funding for virus surveillance and research into EIDs has been frozen and WHO member states have yet to agree a deal on “One Health” – the widely accepted idea that animal and human health are closely connected.

One of the unfortunate consequences of Covid is that rather than uniting the world against the threat posed by new pathogens, it divided countries, fuelling conspiracy theories about EIDs and undermining trust in science. The attacks on figures like Antony Fauci, the former the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the president’s chief medical advisor, also turbocharged Donald Trump’s re-election campaign and boosted Kennedy’s war on vaccine science.

This is not only ignorant but short-sighted. If the Budongo chimps had contracted a new, highly transmissible form of SARS from the guano, rather than Marburg, then in my scenario we could have had another Covid-style pandemic on our hands. That would almost certainly have triggered border closures and lockdowns, making Trump’s present tariff war with China look like a walk in the park.

And all because of a dietary shift in chimps triggered by the global demand for tobacco and US cuts to virus surveillance programmes.

Thank you for your comment. I was compelled to write the piece by my frustration with the US’s present war on public health. Let’s hope these things are cyclical and saner minds will eventually prevail. In the meantime, please tell your friend they’re welcome to use my piece as a teaching aid. I can think of no higher compliment.

This is a chilling, incisive, and superb piece of writing that makes the cost of recent public health decisions all too clear. I sent this to a professor of public health who said your post would make excellent classroom reading. Very well done. Thank you for taking the time to write this.