Reign of Silence

The line for the Queen's Lying-in-State takes mourners directly past a wall adorned with 200,000 hearts dedicated to Britain's Covid dead. So why is the media so silent about their losses?

By the time you have read this article hundreds of people will have filed past the Queen’s coffin in Westminster Hall and many more will have joined the queue snaking through Victoria Gardens. At time of writing that queue stretches across Lambeth Bridge and more than four miles along the south bank of the Thames to Bermondsey beach. By tomorrow it may have reached Wapping.

Were you minded to join the queue this evening, it would take you eight hours to reach the catafalque bearing the Queen’s coffin draped in the Royal Standard at her Lying-in-State.

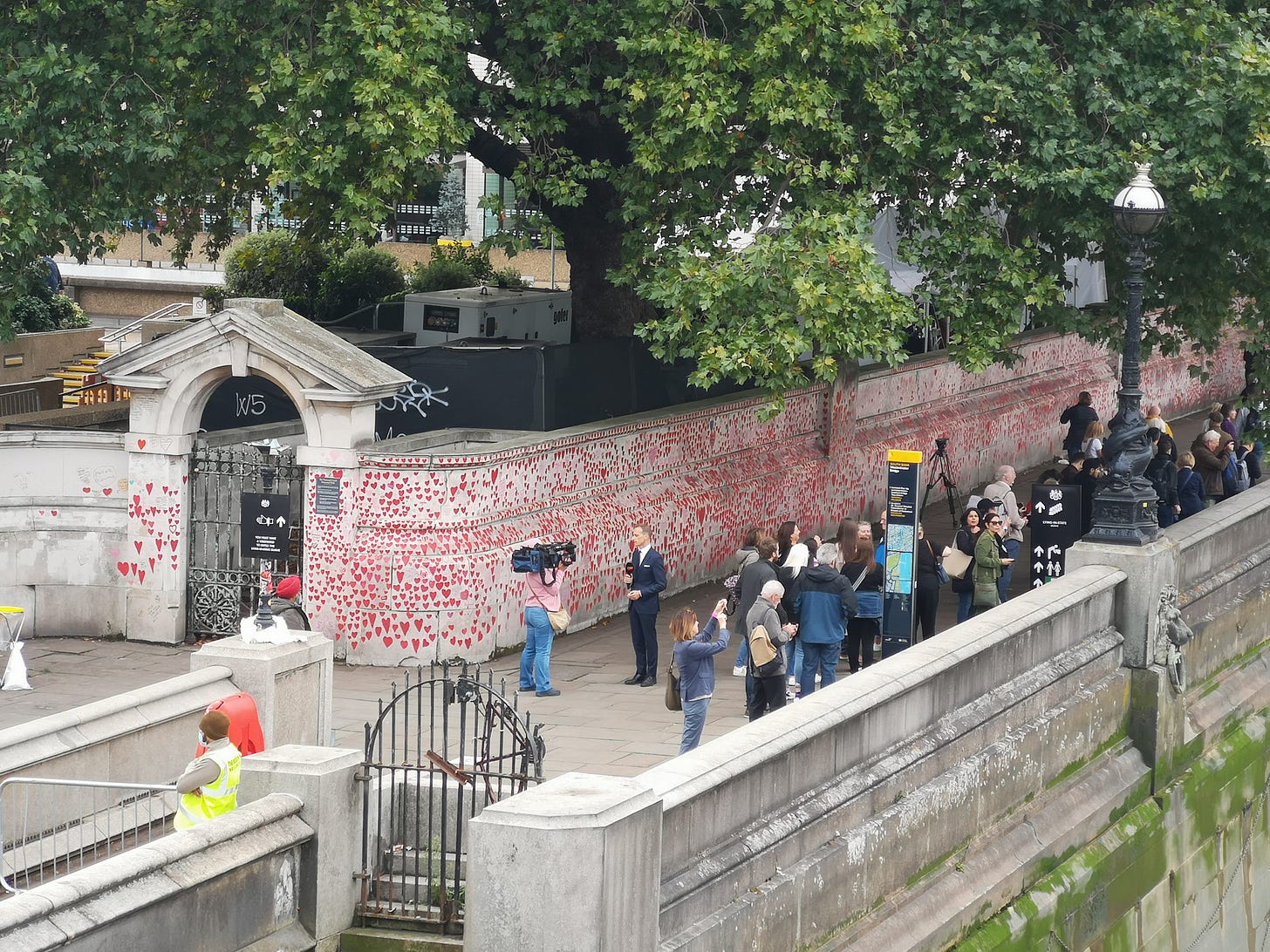

The queue follows a meticulous plan known as Operation London Bridge which has been decades in the making and with which, we are led to believe, the Queen was intimately involved. But even the Queen could not have anticipated that so many people would want to view her coffin, nor that the queue would take mourners past a 500-metre-long section of wall on Albert Embankment adorned with 200,000 hearts commemorating the British victims of Covid-19.

Judging by the people I spoke to in the queue on Thursday lunchtime, about half had no idea what the hearts signified until they reached the end of Albert Embankment and saw a sign identifying it as the “National Covid Memorial Wall”. This is hardly surprising given the suspension of normal political debate following the Queen’s death seven days ago and the media’s reluctance to discuss any subject that might be considered insufficiently respectful of monarchy.

Although the memorial has yet to be officially sanctioned by the authorities, it has been the subject of numerous news reports since the first hearts appeared on the wall in April 2020 courtesy of Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, the activist group instrumental in persuading the government to commission an independent public inquiry into its handling of the pandemic. This was particularly the case during ‘Partygate’ when the memorial proved an irresistible backdrop for broadcasters seeking to illustrate the dissonance between the British public’s observance of the government’s Covid regulations and the flouting of the same rules by Boris Johnson and senior Downing Street officials.

But today, the cameras are all pointed in the other direction – towards Westminster.

As far as I am aware, only ITV has referred to the wall’s juxtaposition with the extraordinary scenes of mourning on the opposite bank of the Thames and how they might resonate with those who have recently lost loved ones to Covid-19. From the BBC, there has not been a peep.

Of course, the media has a famously short attention span and journalists covering the Queen’s funeral arrangements – especially those from US and Australian-based networks – cannot necessarily be expected to spot a good story even when they are standing right next to it. However, as Catherine Mayer, who lost her husband Andy Gill to suspected coronavirus more than two years ago and later dedicated a heart to him, points out, they should at least respect the Covid dead. Instead, when she visited the wall recently she found many journalists using it as a support for their camera equipment.

“I understand journalists not knowing what @CovidMemorialUK is, even though there are big signs on it,” Mayer tweeted on Thursday. “But the news organisations sending them here should absolutely be aware and they should include it in their coverage”.

Volunteers who visit the wall every Friday to restore the hearts, which are in a fragile condition and require constant retouching, but who have stayed away this week out of respect for the crowds mourning the Queen’s passing were similarly disappointed, tweeting how they were “watching this public ignoring of our pain being played out”.

I cannot believe the Queen would have approved the insensitivity shown by journalists or the stultifying media silence on the subject of the Covid bereaved. After all, this was a monarch who, rallying the nation during the first lockdown, spoke of the “painful sense of separation from loved ones” and the promise that though “we may have more still to endure, better days will return”.

At the time the Queen uttered those words, she could not have known that both she and Charles would go on to suffer bouts of Covid and that within a year her husband, Prince Phillip, would be dead of “old age”. Nor could she have known that his death, which came at the end of the second coronavirus wave, would be joined symbolically with the victims of Covid, as this heart dedicated to him on the wall illustrates.

However, as a keen student of her family’s history, she would have known that in 1892, her grandfather George V’s brother, Prince Albert Victor, died suddenly of an influenza-like illness that some scientists now believe may have been caused by a coronavirus. Coming in the midst of an epidemic of “Russian influenza” and shortly before his planned betrothal to Mary of Teck, Prince Albert’s death at the age of 28 stunned the nation and, as today, saw huge crowds attending his memorial service at Westminster Abbey.

“It was as if every man and woman in the kingdom had been overtaken by a great private sorrow,” opined the Graphic, which produced a special ‘double’ memorial issue to mark the occasion. “The more the calamity was thought of, the more sad it seemed, and the more tender became the expressions of sympathy for the dead Prince’s family”.

The Russian influenza epidemic eventually petered out in around 1898 and, although the pandemic of Covid-19 is far from over, the Queen was right to be optimistic: for most of us better days have returned. Despite the energy crisis and the myriad other challenges facing Liz Truss’s government, Britain is no longer in lockdown and the NHS has just begun offering a fourth jab to the over 65s. As a consequence, mourners filing past the Queen’s coffin are no longer required to wear face masks, though judging by the BBC’s live feed of the Lying-in-State some are still opting to do so.

Going by a straw poll I took on Thursday, many of those paying their respects to the Queen this week would welcome a wider discussion of what her death means for the Covid bereaved. “I lost someone to Covid so yes it brings it all home,” one mourner told me. “It’s a chance to reflect on everyone who has died – not just the Queen.”

But for every person who thought it appropriate to open up the debate, there were others who demurred. As another mourner told me, the sight of all the hearts was “very moving” but she thought the Queen’s death was “a separate thing” from Covid and ought to remain so.

Others pointedly expressed the view that what they most admired about the Queen was refusal to get drawn into political debate and that it was time to “put the pandemic behind us and move on”.

Unfortunately, for the 200,000 Britons still mourning the loss of loved ones from Covid “better days” will only be possible once the present period of royal mourning is over and the public inquiry headed by Baroness Hallett begins taking evidence from the bereaved in October.

Until them, I fear the silence around the casualties of Covid will continue to reign.