“On this earth there are pestilences and there are victims – and as far as possible one must refuse to be on the side of the pestilence” – Camus, The Plague

In the dog days of August, as storm Henri made its way up the eastern seaboard of the United States and the Delta variant filled intensive care units in Oregon and Florida to capacity, I found myself standing anxiously in the mosh pit of Joe Pop’s, a cavernous nightclub on Long Beach Island, New Jersey.

The Nerds, a popular local tribute band, were midway through a mash up of Run DMC’s It’s Tricky and Toni Basil’s Hey Mickey and the mostly mask-less young crowd were loving it.

“It’s tricky to rock a rhyme, to rock a rhyme that’s right on time”, hollered the Nerd’s fifty-something lead singer and Buddy Holly look-a-like. “It’s tricky.”

“Oh Mickey, you’re so fine, you’re so fine you blow my mind,” responded the crowd. “Hey Mickey!”

After a year of cancelled gigs and cancelled classes, you could hardly blame the Nerds, or their college-age fans, for wishing to let off steam. But as the strobe lights illuminated the spittle from the lead singer’s strained vocal cords, I couldn’t help but think of the scene in Jaws where the mayor of Amity defies Richard Dreyfuss’s advice to close the beaches and invites holidaymakers to frolic in the surf.

Unless you are a zero-Covid zealot, which I am not, sooner or later all of us are going to have to learn to live with the coronavirus. But it is one thing to accept that SARS-CoV-2 will become an endemic infection; quite another to deliberately swim beyond the lifelines when you know there’s a dangerous predator lurking beneath the surface. With the Delta variant hospitalising rising numbers of people on both sides of the Atlantic, many but by no means all of them unvaccinated, and death counts steadily increasing in the US, in my view this is no time to be taking unnecessary risks.

Located 24 miles north of Atlantic City, LBI is a windswept barrier island with a crab-filled bay on one side and 18 miles of uninterrupted beach on the other. Perfectly positioned to catch the Atlantic swells, LBI is a surfers’ paradise. It’s also the perfect place to escape the gloom of a British summer, especially if – like me – you’re fortunate enough to have in-laws who own a beach house on the island.

So it was that after three national lockdowns and three cancelled trips to Europe due to the UK government’s shifting traffic-light travel system, my wife and I boarded a plane at Heathrow and flew to John F. Kennedy airport, from where we drove direct to the Jersey shore. It was the beginning of a two-week odyssey that would also take us back across the state line to Manhattan and, in my case, to Brooklyn. In so doing, I would be re-tracing a journey taken by thousands of New Yorkers in 1916 when, to escape a polio epidemic then raging in Brooklyn and Manhattan, they’d flocked to the Jersey shore to bathe in the cool, “predator-free” waters of the North Atlantic.

Unfortunately, the waters north of Cape Hatteras are also home to sharks and in 1916 one, or possibly several, mauled a series of bathers holidaying on LBI, killing four of them. Those attacks provided the inspiration for Peter Benchley’s bestselling novel Jaws and Steven Spielberg’s film of the same name, sparking an obsessive – and irrational – fear of great white sharks that persists to this day.

In 2016, when I last visited LBI, the shark attacks – which experts at the time had declared impossible – struck me as a perfect metaphor for the unknown pathogens lurking out there in nature waiting to strike humanity. And so it was that when, five years ago my agent called to say that my book documenting a century of missed epidemic and pandemic alarms had been acquired by publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, I incorporated the story of the shark attacks into the narrative.

At the time, I had no idea that within months of the publication of The Pandemic Century in May 2019 the world would be turned upside down by Covid-19 or that in September 2021, citing Larry Vaughn, the fictional mayor of Amity in Jaws, as his hero, the UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson would resist calls from his scientific advisers for a second national lockdown, sending an additional 56,000 Britons to their deaths on top of the 44,000 who perished during his botched management of the first wave.

Following the lifting of the UK’s remaining social distancing restrictions in July, I was looking forward to escaping Johnson’s blighted island and revisiting the coastline that had inspired my book. I also thought it would be a good opportunity to gauge how politicians and populations on both sides of the Atlantic were navigating the growing threat from the Delta variant in the run-up to the reopening of schools and college campuses in the fall.

What I saw on LBI instilled little confidence. Manhattan was more encouraging, Brooklyn more encouraging still. The biggest shock, however, came when I returned to Heathrow.

In contrast to the UK’s national lockdown in spring 2020, which coincided with endless blue skies, the weeks and months that followed Johnson’s declaration of “freedom day” on 19 July 2021 were mostly subdued and overcast. But for someone who has made a close study of the history and science of pandemics, the summer was also depressing for another reason: thanks to the UK government’s mixed messaging, most Brits seemed to think the pandemic was over and had stopped wearing face masks in shops and taking other elementary precautions.

But unfortunately, the pandemic isn’t over. While cases may have slowed in recent weeks in the UK, Italy, Spain and France, globally they are increasing faster than ever, propelled mainly by new cases in South America and Southeast Asia, where vaccination coverage is perilously low and there are insufficient supplies of vaccines. Worse, in recent weeks cases across Europe and North America have been ticking steadily upwards.

The US figures are particularly alarming, with more than 100,000 people being hospitalized with coronavirus every week – higher than in any previous surge except for last winter when most Americans had yet to be vaccinated. The crisis is particularly acute in Oregon, where the National Guard have been dispatched to hospitals straining to cope with an influx of gravely ill patients. The result, at time of writing, is that Oregon has more cases than at any point in the pandemic. Nor is the situation much better in Florida, Mississippi and Louisiana, three of the hardest hit Southern US states where ICUs are currently operating at close to or full capacity.

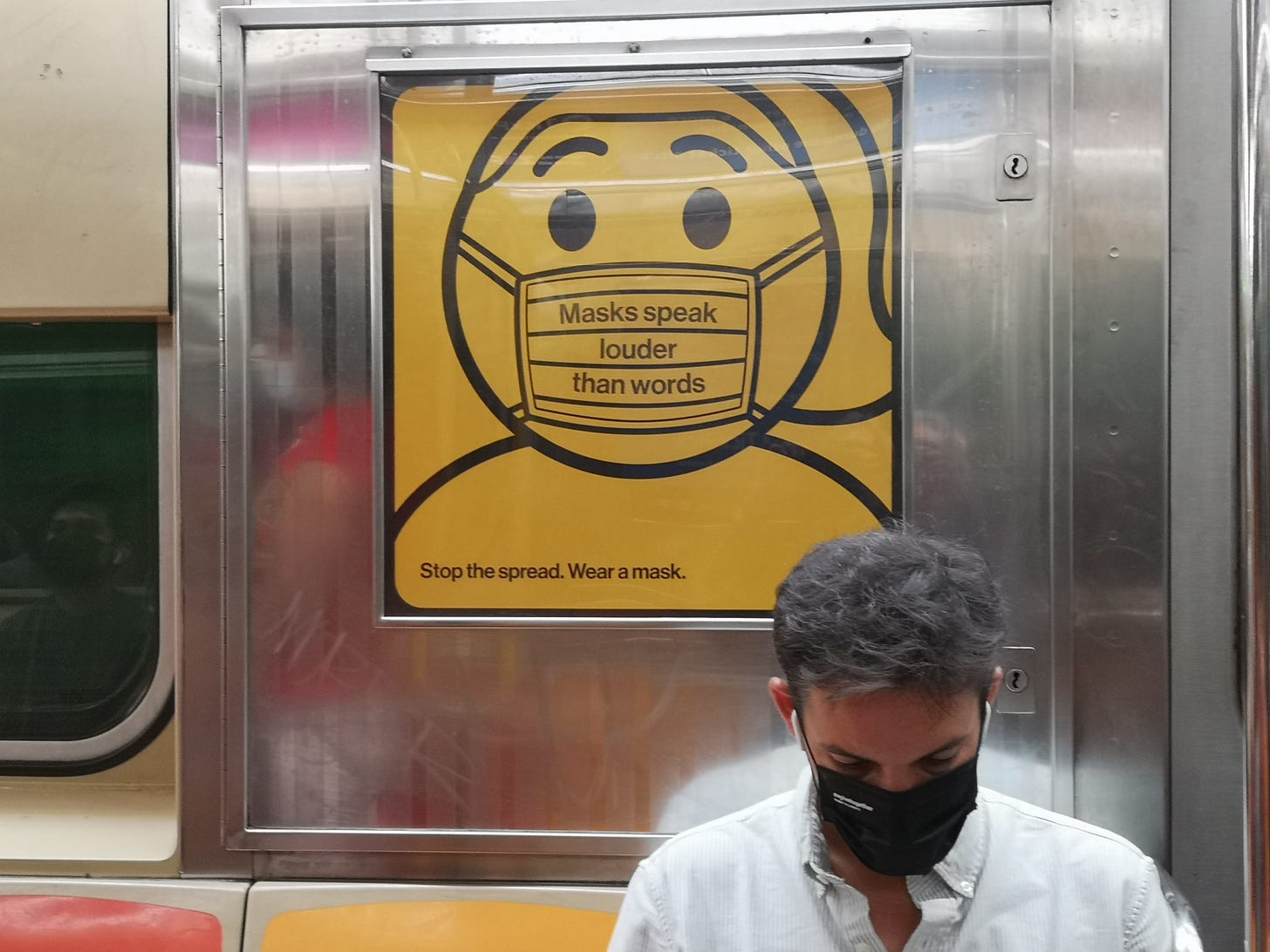

With the exception of Oregon, where the governor has made mask-wearing compulsory in shops, restaurants and congested public spaces, all the worst-hit states are led by Republican governors opposed to face masks. The worst offender is Florida, where Ron DeSantis has prevented local governments and school districts from issuing mask mandates, saying parents ought to be able to decide for themselves. This, despite the risk that unvaccinated, mask-forsaking individuals present to other people, especially children and those with asthma and other pre-existing conditions.

Not all governors are as ideologically blinkered as DeSantis: New Jersey’s governor Phil Murphy, a Democrat, recently directed that children will be required to wear face masks when they return to school in the fall in line with advice from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Unfortunately, as I discovered when I arrived at the Jersey shore, Jersey’s rules do not extend to young adults or older age groups – hence the absence of masks inside Joe Pop’s. Sadly, it was much the same when I visited the luncheonette near my in-laws’ beach house in Harvey Cedars and received a frosty stare from a mask-less customer seated at the counter.

The result was that, as in the UK, where the government has also made masks discretionary, few people holidaying on the Jersey shore seemed to be concerned about covering-up or, to judge by the shoppers crowding the aisles at Ron Jon’s, a popular local surfing apparel store, observing the two-meter rule.

Little wonder that after three days at the shore I also began to lower my guard – after all, who wants to don a mask while basking in the sun and breathing the ozone-rich air from the Atlantic? And that, dear reader, is how I came to find myself swigging a beer at Joe Pop’s as the Nerds revisited their playlist from care-free times-gone-by.

In retrospect, none of this was “fine” and at the set break my wife turned to me and said: “This is a Covid clusterfuck”. We exited the bar. There was nothing “tricky” about it. As Camus puts it in The Plague: “On this earth, there are pestilences and there are victims – and as far as possible one must refuse to be on the side of the pestilence.”

At the set break my wife turned to me and said: “This is a Covid clusterfuck”. We exited the bar. There was nothing “tricky” about it.

I’m pleased to say Brooklyn couldn’t have been more different. It wasn’t just another state; it was a parallel world. Emerging from the Grand Armée subway stop, I paused to allow a group of pre-schoolers and their carers to pass. Though it was a broiling 80 degrees, all of them were masked. As they ambled toward Prospect Park, I watched as an elderly couple, also wearing face masks, varied their step, then swerved to avoid them.

These scenes, which after a week at the shore struck me as surreal and overly cautious, continued as I descended Park Slope, past masked moms and their coddled infants. Even more surreal was the sight that greeted me at sunset when rats began to emerge from beneath parked cars to forage for food. To my horror, one particularly bold specimen halted before a discarded carry-out container in my path, then bounced it along the sidewalk as its tail flicked hungrily from beneath the lid.

I was told that the rodents’ behavior was the result of a lockdown-fuelled construction boom in Brooklyn which has seen the streets adjoining Atlantic Avenue torn up to provide services for new condominiums and offices at Atlantic Yards.

The sudden appearance of rodents on their doorsteps has horrified local residents. “I've seen rats in the park before, and by construction sites, but to have two race right by the door. . . I'm shaking!”, moaned one Park Slope resident. Unlike the rodents in Camus’ The Plague, however, there seems little danger of Brooklyn’s rats dying in “some well-contented city”. On the contrary thanks to the growth of carry-outs and ready meals they are fatter and fitter than ever.

Until now, no one anywhere had asked me for my vaccine pass, not even at immigration at JFK (on the flight from London, we’d been instructed to fill out a New York state health travel form but when I tried to hand it to a customs officer at the exit from the baggage hall she refused to take it and waved me through). This was odd, as my arrival had coincided with New York becoming the first city in the US to require patrons of restaurants, gyms and indoor entertainment venues to present proof of double vaccination.

In theory, the order was due to be enforced on 13 September to give businesses time to get used to the procedures (unlike in the UK, where nearly everyone has the NHS app, in New York people have only just begun downloading the equivalent Excelsior Pass). But as I soon discovered when I ordered a beer at a bar on Fifth Avenue, Brooklyn was an early adopter.

It was the same at Café Regular, a popular breakfast spot for writers and ex-pats (the café boasts a rack filled with recent editions of the London Review of Books) where I was again asked for my pass (this time I was ready and had downloaded the pdf with the QR code to my phone for faster access). On that occasion I took my coffee and bagel outside, but the next day I returned and sat at a banquette, the better to study a large mural on the wall depicting a crowded Parisian street scene bearing the legend: L’enfer c’est les autres. The phrase is from Sartre’s play Huit Clos and is usually translated as “hell is other people”. After twenty months locked up with only our phones and families for company, it struck me as an apt metaphor for the bind we find ourselves in as we try to resume something like a normal social life.

In Sartrean terms, we only become truly free, conscious beings in the world when we expose ourselves to the objective gaze of other people. Without such scrutiny there is little chance of escaping our subjective viewpoint or psychological growth. But other people can be hell, particularly when they force us to view ourselves as others see us.

This is especially the case at a time where in one jurisdiction wearing a mask can be seen as a sign of respect and elicit a friendly nod and in another it can provoke outright hostility. In Ocean County, the district that covers LBI and other points along the Jersey shore and where Trump voters outnumber Biden supporters 2:1, my mask marked me as a political progressive and an object for scorn. By contrast, in Brooklyn, the failure to wear a mask can get you cancelled quicker than you can say “Kevin Spacey”.

However, at least in the United States you know roughly when and where you should don a mask and when you are free to exercise your own judgment. Not so the UK where the government’s laissez-faire policy has become a recipe for confusion.

Arriving back at Heathrow, I was struck by how many people milling around the baggage hall were mask-less. This, despite prominent signs in Terminal 5 making it clear that masks are mandatory at all times in airport buildings. Nor was I any more reassured when, shortly after touching down, I learnt that the UK’s Education Secretary Gavin Williamson had refused to make masks mandatory in classrooms and that, having stated in January that the government had no plans to introduce vaccine passports, the vaccine minister, Nadhim Zahawi, had performed a U-turn and announced that the government would be requiring the passes in nightclubs and other indoor venues from the end of September.

Clearly, Sartre’s phrase is in need of updating: hell is not only other people, it is one’s own government.