Killing science, resurrecting viruses

Trump's decision to dismiss 1,200 employees of the National Institutes of Health will undermine scientists's ability to conduct cutting-edge research into pandemics and how to prevent them in future.

New readers of Going Viral may not realise that this newsletter began life as a podcast on a different platform. With the news this week that Trump is to dismiss 1,200 employees of the National Institute of Health (NIH), including scientists whose research is vital to understanding pandemic pathogens, I am importing all the episodes to Substack and making them freely available via the tab, Going Viral_the podcast

There you will find more than 20 episodes covering everything from the science and politics of Covid-19, to the ethics of the pandemic response to the history of vaccines.

You could do worse than start with“Resurrecting the Killer”, in which I describe one of the most important pieces of research ever conducted by NIH scientists – the sequencing of the genome of the 1918 “Spanish flu” virus - so-called because the first reports of the infection came from Spain.

Within weeks of the virus’s emergence in April 1918, however, outbreaks were also being reported in France, Britain and North America, and by the end of 1919 the virus had killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, making it the deadliest pandemic of modern times.

Until the early noughts, the question of where the H1N1 virus came from, how it got into humans, and why it proved so virulent was thought to be unanswerable.

“It has been the dream of scientists working on influenza for over a half century to somehow obtain specimens of the virus of Spanish influenza, but only something as unlikely as a time capsule could provide them,” wrote the historian Alfred Crosby in his magisterial 1976 study of the pandemic, Epidemic and Peace (later reissued as America’s Forgotten Pandemic).

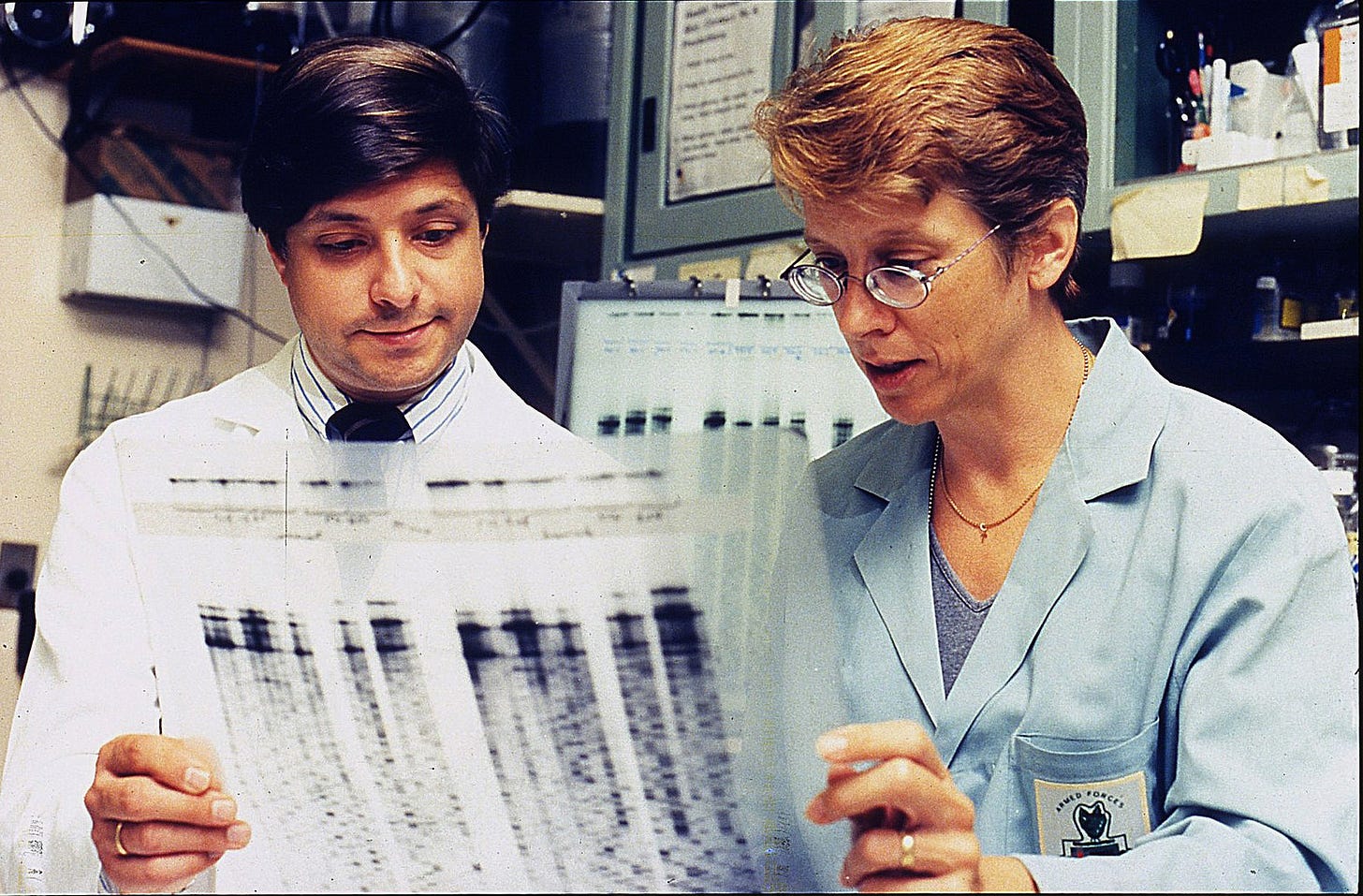

Then in 2005, Jeffery K. Taubenberger, a molecular pathologist who now heads the NIH’s Viral Pathogenesis & Evolution Section, and his colleague, Ann Reid, announced they had sequenced the virus’s genome and that colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were conducting animal studies in attempt to figure out what had made it so deadly.

To resurrect the virus, Taubenberger and Reid had screened lung autopsy material taken from American soldiers who had died of influenza in 1918 and which had been preserved in paraffin wax at the Walter Reed Army Institute for Research in Bethesda, Maryland, not far from NIH. However, the key specimen had come from an obese Inuit woman, known as “Lucy”, who had been buried in 1918 in a mass influenza grave overlooking the Seward Peninsula in Alaska.

The permafrost had preserved just enough of Lucy's lung tissue to enable Taubenberger and Reid to fish out fragments of the virus. By amplifying the viral RNA using polymerase chain reaction and combing it with fragments retrieved from two American soldiers, they were able to reconstruct all eight of the virus’s genes.

The perseverance required to screen thousands of autopsy remains in the hope that one or two would contain samples of the extinct virus is admirable, and you will not be surprised to learn that Taubenberger and Reid very nearly gave up. That they didn’t is testimony to their belief in the value of their research and NIH’s willingness to support it.

Although their study did not resolve the question of where the pandemic originated, an analysis of the virus’ genome strongly indicated it had mostly likely begun as an infection of wild birds. As Taubenberger told me when I visited him at NIH in 2018 on the centenary of the pandemic, the 1918 virus was one of the most “avian-like” mammalian influenza viruses he’d ever encountered. So much so that he could not discount the possibility that it had jumped directly from birds to humans.

Following the publication of the genome, scientists at the NIH and CDC reconstituted the virus and infected mice and ferrets with it in an effort to understand what had made it so virulent. The scientists were also able to design a vaccine to neutralise the virus, something that could prove vital should a similar virus emerge from nature again, or should H5N1 bird flu become transmissible as an aerosol – something that, thankfully, has yet to happen (for more information on how likely this is, see my recent interview in The Observer with Wendy Barclay, a virologist at Imperial College, London).

At a time when the H5N1 bird flu virus is infecting backyard poultry across North America and the virus has spread to dairy cows in 16 US States, causing sporadic human infections and, on occasion, deaths, Taubenberger’s research is as significant as ever. All the more pity then that Trump and his acolytes seem determined to frustrate the ability of Taubenberger and other NIH scientists to conduct similar research in future.

Going Viral and Going Viral_the podcast are only made possible by support from you, the reader. To continue reading and listening to my output, please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

Mark, NIAID funded DARPA Defuse in 2018-19 and Covid was an animal vaccine:

https://jimhaslam.substack.com/p/fauci-funded-darpa-defuse-for-141m

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5d-eqdRSx7Y