Is the media working?

At an invitation-only event in London this week, journalists lamented the slow death of their profession and wondered what the hell they should do about it.

There is a well-known adage in journalism, known as Betteridge’s Law, that states that “any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no." So it was that pitching up a hotel in Leicester Square this week for a discussion entitled, “Is the media working?”, I already knew the answer.

I’m pretty sure everyone else in the room did too. Which is partly what had brought us together: journalists love a good moan and there’s nothing like safety in numbers when the liberal order has just been dealt a hammer blow by a pumped-up reality TV star and convicted felon.

But that was last week’s news. The real question, wondered Julia Hobsbawm, was what the hell we were going to do about it?

Julia, who I have known since the glory days of Britpop and Tony Blair – a time when we naively thought “things could only get better” – is a supreme networker with a knack for persuading journalists to step away from their screens and mingle with people from the worlds of business and public relations. She’s also no slouch when it comes to disseminating her opinions – besides publishing books on the future of work, she has a podcast and writes a regular column for Bloomberg. She also has a consultancy called Workathon.

Workathon’s mission is to help clients “tackle the volatility around work” in a world being transformed by Artificial Intelligence and social media. And who better to start with than a bunch of superannuated journalists looking at the slow death of their profession and their seeming irrelevance in the age of TikTok.

To help us navigate these issues Julia had reached deep into her contacts book with a panel featuring Sam McAlister, the Newsnight booker who helped secure the interview with Prince Andrew immortalised in the Netflix film Scoop; Matthew d'Ancona, editor-at-large of The New European; and Ravi Mattu, managing editor of The New York Times’s business newsletter, Dealbook. The invitation-only audience also included Stephen Sackur, the presenter of BBC News’ HARDtalk, which the corporation recently announced it was axing after nearly three decades on air; Katie Vanneck-Smith, the CEO of Hearst UK; and Carole Cadwalladr, The Observer feature writer who exposed the illicit funding of the Vote Leave campaign in the 2016 European referendum, as well as Facebook and Cambridge Analytica’s role in Donald Trump’s election victory the same year.

Though Julia did not define what she meant by the term “media”, everyone in the room knew we were talking principally about the decline of legacy media and what Walter Lippmann in his seminal 1922 book, Public Opinion, identified as journalists’ critical role in transmitting trustworthy information to the public. The experience of the First World War had taught Lippmann that propaganda presented an existential threat to Western democracies and that it was the duty of journalists to guard against the opinions of the “bewildered herd”. Professionally trained journalists, thought Lippmann, were best qualified to distinguish between truth and lies and parse the information required by the public to make informed decisions. The problem is journalism is also a business and most people are unwilling to pay for high quality information. "For a dollar, you may not even get an armful of candy,” wrote Lippman. “But for a dollar or less people expect reality/representations of truth to fall into their laps."

And that, more or less, has been the story of journalism ever since. The difference today is that whereas in the past there were all sorts of barriers to entering the media, now anyone with a smartphone can call themselves a journalist and broadcast whatever they like to anyone, anywhere in the world at any time. Worse, some members of the media have bigger megaphones than others (stand up Elon Musk) and through their manipulation of algorithms can game the information landscape to their - and their preferred candidate’s - advantage.

But what makes Musk and Trump’s bromance so dangerous is that X has now effectively become, as Cadwalladr puts it, a “tool of the state”. In addition, politicians no longer need to go on CNN or the BBC to get their views across. Instead, they can speak directly to the public via friendly podcasters such as Joe Rogan. And even when journalists like Sackur manage to briefly hold presidents and prime ministers to account, those same politicians know that few people will ever watch the full BBC interview. Instead, they cut and paste the segments that cast them in the best light and disseminate them via their own propaganda channels.

Of course, demagogues like to claim it is not they that are fake but the liberal news media. As McAlister pointed out, Trump’s employment of the term “fake news” was the beginning of the end for Newsnight and other legacy media shows. Portraying herself as one of the few people at Newsnight to have had her finger on the public pulse, she argued there was no going back to the before times. “I don’t read newspapers or books any more yet somehow I still know what is going on,” she explained.

Another of Julia’s guests, whose name I did not catch, argued that the legacy media had been slow to realise that in the new media landscape it was all about holding people’s attention and that the reason Trump had granted Rogan a three-hour interview is that Rogan understood this “attention economy” better than anyone. This produced nodding all round, including from the journalists in the room who had recently launched their own podcasts.

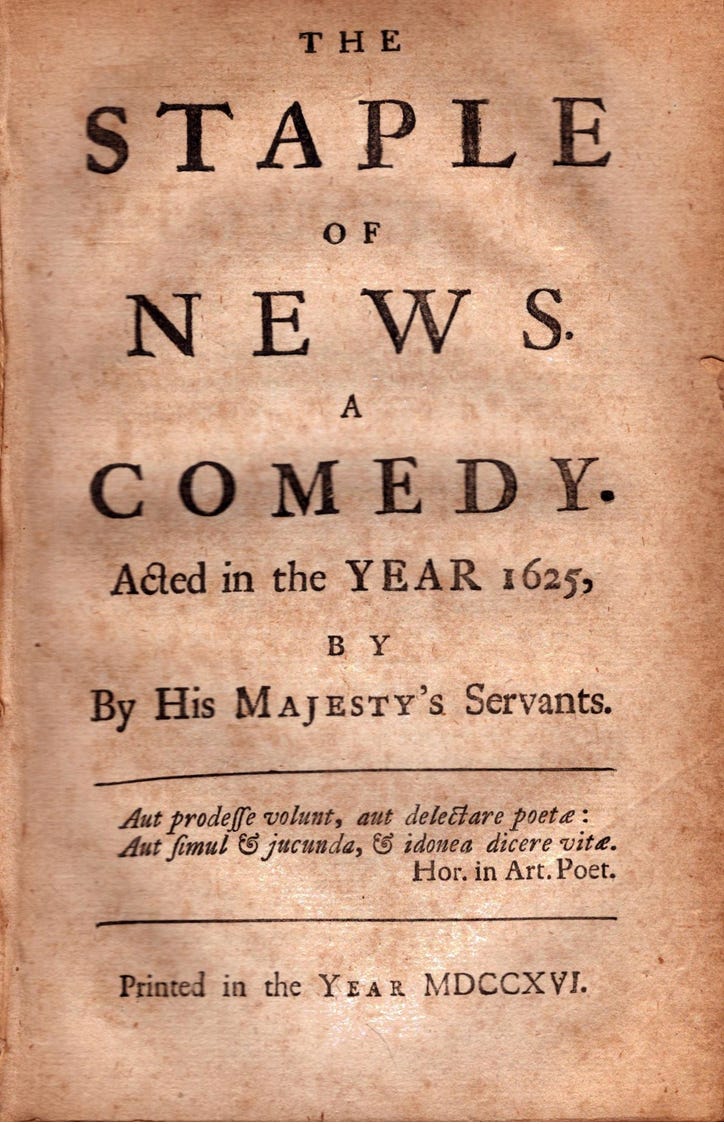

Perhaps the most interesting point of all came from another speaker from the floor who, paraphrasing Ben Jonson, lamented that some people seem to believe anything they read these days. The quote he was referencing comes from Jonson’s 1625 play, The Staple of News. I used to cite it in my history of journalism lectures at City, University of London, and it is worth reproducing it in full as it is easily misunderstood. Jonson wrote:

“See divers men’s opinions, unto some

The very printing of ‘em makes them news:

That have not the heart to believe any thing

But what they see in print.”

The point Jonson was making was that whereas in earlier centuries news had been conveyed by word of mouth, with the invention of the printing press in 1440 and the advent of printed pamphlets and periodicals in the sixteenth century, news became inextricably linked with the new medium of print. And because the technology was so novel and beguiling, people assumed that every word in print must be true. This is the opposite of today where anyone who believes what is written in a newspaper or on a legacy news platform risks being derided as naive or as a “blue-piller”.

But of course, there is no such thing as “fake news”. There is only news and propaganda. And the challenge for professional journalists is to convince the public they are purveyors of the former.

The question is how to do so in a world where expertise has become a dirty word and trust is in short supply. The answer, I think, is to recognize that we have come full circle. As the historian Andrew Pettegree argues in his book, The Invention of News, our medieval ancestors had a profound suspicion of information that came to them in written form, just as many people do today. Instead, the public were far more likely to believe a report that came to them verbally, especially when the news was delivered by someone they trusted, such as a priest, or by a practised entertainer, such as a travelling minstrel.

The problem is that the minstrels and jokers people look to today for “representatons of the truth” are people like Rogan and Trump. Changing that will not be easy - it will require work. But we can make a start by recognising that these days it is not only the medium that is the message but also the messenger.

Brilliant piece Mark. Perhaps there will come a time when critical thinking skills become discerning enough to separate news from propaganda. Cautiously hopeful that the success of platforms for independent writing may save us?