Having funakka on Hunakkah

With so much grim news this holiday season, the ‘Chanukah Song’ always succeeds in putting a smile on my face.

As the nights draw in and all around me people call for the globalization of the intifada, I’ve been cheering myself up by streaming Adam Sandler’s ‘Chanukah Song’. As a secular Jew (who doesn’t own a menorah), for me Sandler’s upbeat novelty song is the equivalent of lighting a candle in the darkness. And boy, are times dark.

At the university where I teach, one of my Jewish students was singled out for wearing blue-and-white trainers, which pro-Palestinian students interpreted as a sign he was a Zionist.

Meanwhile, the presidents of Harvard, Penn and MIT cannot bring themselves to unequivocally condemn speech calling for the genocide of Jews, saying that whether or not it infringes their codes of conduct is a matter of “context”.

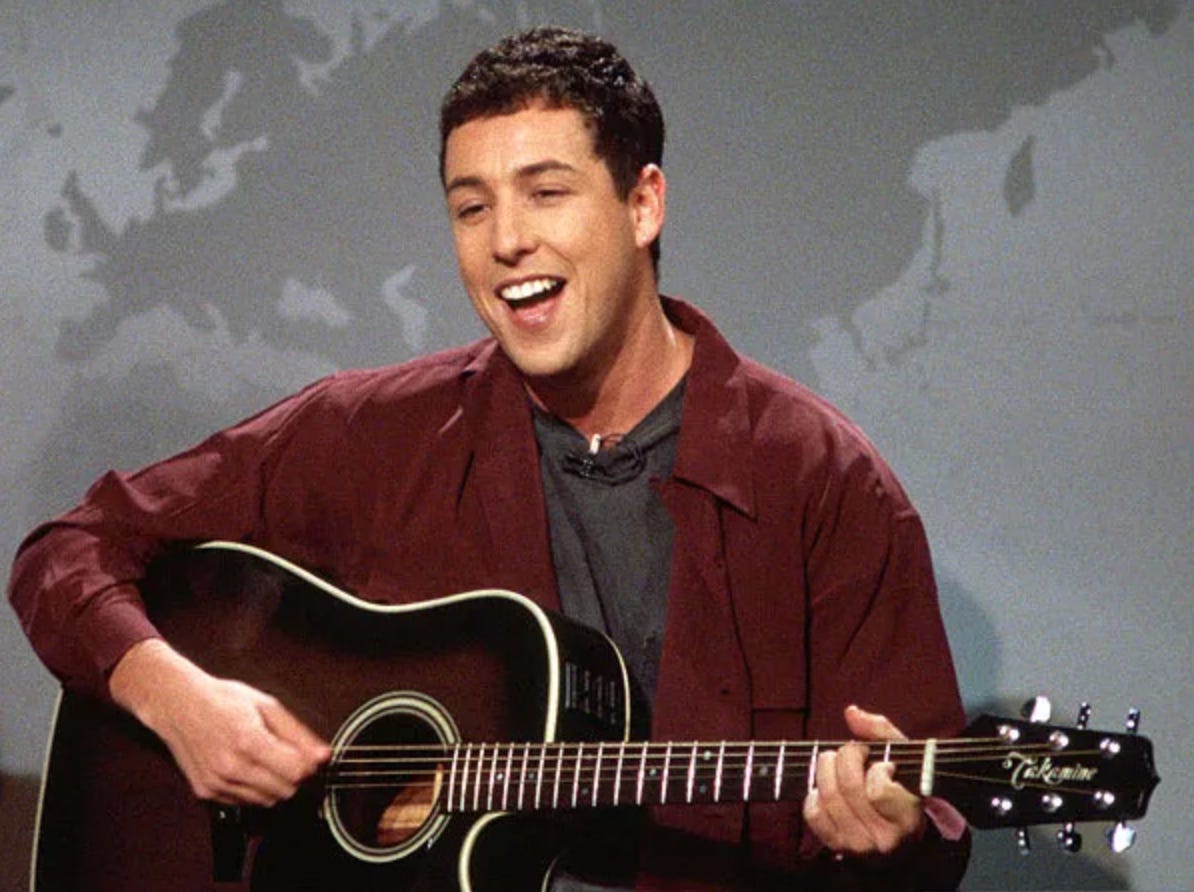

Thank God for our secret weapon: comedy. It was my wife’s idea that during Hanukkah, we stream Sandler’s song. First performed on ‘Saturday Night Live’ in 1994, the Chanukah Song is Sandler’s riposte to popular Yuletide favourites such as ‘Jingle Bells’ and ‘Frosty the Snowman’ and a celebration of Jewish celebrities and sporting heroes.

“There's a lot of Christmas songs out there and not too many Chanukah songs, so I wrote a song for all those nice little Jewish kids who don't get to hear any Chanukah songs,” explains Sandler in his preamble.

With its joyful refrain, “Put on your yarmulke/Here comes Chanukah/It’s so much funnaka”, Sandler cleverly reinvents the Jewish festival of lights for Jewish and non-Jewish audiences alike, boasting: “Instead of one day of presents, we have eight crazy nights”.

However, Sandler also does something that I’ve never heard a British artist do: he reclaims the identities of Jewish-American celebrities hiding in plain sight and makes them proudly visible. Or as Sandler puts it: “When you feel like the only kid in town without a Christmas tree/Here's a list of people who are Jewish just like you and me.”

What follows is a list of pop stars and celebrities, from David Lee Roth to James Caan, and Calvin Klein to Goldie Hawn, who are Jewish, half-Jewish or in the case of Harrison Ford, supposedly a quarter Jewish (“not too shabby”). So popular is the song in the United States, that it runs to several versions, with Sandler adding and subtracting new lyrics each time.

Everyone will have their favourite lines but the ones that never fail to bring a smile to my face are:

“Lenny Kravitz is half Jewish

Courtney Love is half too

Put them together

What a funky bad ass Jew”.

Listening to the song again this Hanukkah, I scoured my mind for British-Jewish equivalents. The choice is not nearly so wide. Mick Jones from The Clash and Amy Winehouse perhaps? Or Stephen Fry, who though raised an atheist is the grandson of Hungarian Jews. Or former Bond girl Jayne Seymour, who, as I learnt when I Googled her, was born Joyce Penelope Wilhelmina Frankenberg, the daughter of a Jewish gynaecologist and obstetrician.

I was also surprised to learn that David Beckham is a quarter Jewish through his maternal grandfather, Joseph, and considers himself very much “a part of the British Jewish community” (having been vilified for that tackle on Diego Simeone at the 1998 World Cup he certainly knows what it’s like to be a scapegoat). But perhaps the biggest surprise of all was the discovery that my teenage idol Marc Bolan was half-Jewish.

I can still recall the moment I first saw Bolan live on Top of the Pops. It was March 1971 and as I did every Thursday evening, I turned on the TV to see who was rising in the charts. Dressed in a silver jacket with glittery gold teardrops beneath his eyes, Bolan was, to use the jargon of the time, “outasight”. When he crooned the words to ‘Hot Love’, I was captivated, even though, aged ten, I wasn’t certain what he meant by “she’s my woman of gold,” and “I love the way she twitch”.

In the months and years that followed, I read everything about Bolan I could get my hands on. In New Musical Express, I learned that he had been born Marc Feld and that he’d grown up in Stoke Newington. I also read that his mother, Phyllis, ran a stall in Berwick Street Market in Soho, which is where, presumably, he’d gotten his stylish dress sense.

However, I had no idea that his father, Sid Feld, was an Ashkenazi Jew, and that, like me, his forebears had emigrated from the pale of Ukraine in what was sometimes Russia, sometimes Poland. They didn’t include those details on T-Rex’s album sleeves. Nor did they feature in my sister’s edition of Jackie, which carried pen portraits of every rising pop star from David Cassidy to Donny Osmond.

Perhaps this says more about my ignorance at the time of the British Jewish community of which I was a part. But I think it also speaks to something particular to the British-Jewish experience – and that is that, unlike American Jews, who are for the most part out and proud, we British Jews tend not to advertise our family origins unless specifically asked about them.

Since the October 7 attacks, I have been surprised to discover that several of my colleagues are Jewish, or part Jewish, but that our Jewishness was not something we had felt the need to discuss before.

Given that Jews comprise just 0.5 percent of the British population – by comparison, Muslims comprise 6.5 percent – such reticence makes sense. This is especially the case as British Jews are widely regarded of having a disproportionate influence on the media, not least by ‘supposed’ allies such as Boris Johnson, who marched with British Jews in protest against antisemitism three weeks ago but whose 2004 novel, Seventy-Two Virgins depicts Jews as being able to “fiddle” elections.

The other explanation, I suspect, is that unlike in Germany after the Holocaust, Britain never had to reckon with the Jew hate which, beginning with the 1144 blood libel and the massacre of Jews in York in 1190, is part of our history and culture.

Another factor is that whereas American Jews tended to keep their names on arrival in the US – my father’s family, is a case in point, retaining the name Honigsbaum, rather than anglicizing it to Honeytree, when they landed at Ellis Island in 1888 - most British Jews adopted Christian-sounding surnames, meaning they were able to stay largely under the radar.

But I suspect the biggest factor may be snobbery: as George Orwell observed in his 1945 essay Antisemitism in Britain, “among educated people, antisemitism is held to be an unforgivable sin.” However, while the British middle and upper classes go to great lengths to avoid being seen as antisemitic, we know that distrust or dislike of Jews is always lurking under the surface. However, rather than confronting such prejudices head-on, we downplay our Jewishness, thereby sidestepping any potential un-pleasantness.

Well, no more. Thanks to the refusal of progressives - and the BBC - to describe Hamas’s murderous attacks on October 7 as terrorism, and the cries of “genocide” on our streets, we no longer have the luxury of sitting on the fence.

So, on this, the second-to-last night Hanukkah, “put on your yarmulka” and come and light a candle with me. I think you’ll find it’s funnaka.