On 11 November 1918, Ethel Robson set off from her home in Coventry in a funeral cortège carrying the bodies of her dead mother and seven-year-old sister. It was Armistice Day and the streets of Coventry, like those of other British cities, rang with bells and hooters and “all sounds of celebrations”, she recalled. “But how silent people stood who realized it was our funeral”.

Armistice Day marked the formal end of hostilities with Germany and brought closure to the First World War. But it was also the nearest Britain came to marking the end of the “Spanish” influenza, a pandemic that would kill an estimated 228,000 Britons - nearly as many as had died at the Third Battle of Ypres.

Then, as now, people were keen to put the pandemic behind them and resume their pre-war routines. But while the war was over, the pandemic was not (it continued into 1919), and soon the obituary pages of The Times were filled with the names of soldiers who had survived the killing fields of Flanders and Northern France only to felled by influenza on their return to civilian life.

As Britons look forward to “Freedom Day” on 24 February and the lifting of the UK’s remaining coronavirus restrictions, it is tempting to believe we have reached a similar end point: that it’s now safe to crowd into football stadiums and pubs again without recourse to face masks, lateral flow tests, and all the other paraphernalia we have come to associate with two years of lockdowns.

According to the UK health secretary, Savid Javid, “we are entering into the phase of endemicity” when coronavirus will become just another seasonal respiratory infection, like influenza or the common cold.

But, unlike wars, pandemics do not lend themselves to neat narrative endings. And while the re-framing of Covid as an “endemic” disease sounds as if it is grounded in science, the distinction between endemic and epidemic has always been somewhat arbitrary. For instance, in 1951, Britain suffered 50,000 “endemic” influenza deaths, more than perished in either of the subsequent 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics. And in Liverpool, where the endemic/epidemic strain is said to have originated before spreading to North America, the outbreak was responsible for the highest weekly death toll in Liverpool since the great cholera epidemic of 1849.

Indeed, medical historians argue that the distinction between endemic and epidemic is rooted in colonial-era epidemiology and dates back to the 1850s, when British epidemiologists sought to frame diseases such as cholera, malaria and plague as endemic to Asia and other outposts of Empire. The irony is that this notion of endemicity is now being deployed by populist politicians keen to draw a line under the pandemic and distinguish their polities from those, such as Hong Kong, where, due to sub-standard vaccines, vaccine supply problems, or high levels of vaccine hesitancy, Covid continues to cause large numbers of hospitalizations and deaths. It also glosses over the fact that each day hundreds of people continue to die from “endemic” Covid in Britain and other countries which claim to have got Covid licked.

In previous pandemics, the question of endings rarely, if ever, arose. For instance, in 1831-32, 1848-50, and 1865-67, Britain was swept by repeated waves of cholera – in the 1849 epidemic alone some 14,000 Londoners perished from the disease. Better sanitation and the provision of piped water to cholera-prone neighbourhoods gradually saw the retreat of cholera from Britain and other parts of Europe, but as late as 1892 Hamburg was hit by a devastating outbreak of cholera that killed 10,000 people in the space of just six weeks. Little wonder that medical historians refer to the middle and later decades of the nineteenth century as the “Cholera Years”.

Similarly, in the 1890s successive waves of “Russian influenza” – so-called because the first reports of the pandemic came from St Petersburg – swept the globe, causing high mortality in older age groups and leaving others enfeebled by peculiar neurological conditions reminiscent of long Covid. In 1890, thinking the Russian flu over, the British government commissioned an official report on the pandemic. But the pandemic wasn’t over: further waves of illness swept the British isles in 1891, 1892, 1893 and 1895, prompting one writer to described the flu as the “sphinx of epidemic diseases”.

Nor was there any one day when we celebrated the end of HIV/AIDS. In the 1990s, the first generation of protease inhibitors seemed to promise that it was only a matter of time. By the turn of the century people with HIV were no longer dying of opportunistic infections at the same rate, and thanks to AZT and other drugs, many were living near normal lives, but a vaccine for HIV never materialised. Indeed, HIV continues to kill 680,000 people globally each year. As David France writes in his book How to Survive a Plague: “It was not over. It would never be over. But it was over”.

Premature foreclosures, false endings

Today, we are seeing a similar false ending. The British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s claim to have “got Covid done” is not an end at all but what the medical historian Robert Peckham calls “a spurious foreclosure’. Or as the respiratory disease expert Peter Openshaw put it on the BBC’s World at One recently: “It would be wholly wrong to say the pandemic was in any way over.”

Pandemics only truly end in a social sense when they cease to demand collective societal responses. As the crisis abates and we are no longer required to “stay home” in order to protect fragile health services from collapse, so we begin to drink the waters of Lethe and consign the pandemic to what the historian of memory Jay Winter calls “the category of non-events”. Introducing a new collection interrogating “the forgotten and unforgotten” Spanish flu of 1918-1919, Winter reminds us that it is hard to locate meaning in a natural phenomenon outside of human agency and control. This is particularly the case when, as in 1918, a pandemic coincides with a world war, overshadowing mortality on the home front and making it difficult to comprehend the pandemic virus’s global sweep and delineate it as a discreet disaster.

“So vast was the catastrophe and so ubiquitous its prevalence, that our minds, surfeited with the horrors of war, refused to realize,” opined The Times in 1921. “It came and went, a hurricane across the green fields of life, sweeping away our youth in hundreds and thousands and leaving behind it a toll of sickness and infirmity which will not be reckoned in this generation.”

According to Hayden White, historical consciousness starts with the ability to construct a narrative from a mass of seemingly random occurrences. To comprehend an epidemic or a pandemic as a social phenomenon, we need to give it dramaturgic form, hence the search for the “patient zero” or some other malefactor (the “China virus”) on which to pin the blame. But while the dramatic arc of a pandemic from progressive revelation to crisis and recrimination, seems to conform to a three-act Greek tragedy, the moral is often hard to draw. Writing in the same collection as Winter, the memory studies scholar Astrid Erll argues that storytelling in the framework of modern memory requires heroes and villains. “But who are the perpetrators if the Flu is caused by mutations of string of RNA? What could the moral of the story be if victims are claimed randomly?”

Perhaps that is why, when in 1920, Britain’s Minister of Health asked the Chief Medical Officer, George Newman, to compile a report on the pandemic, its meaning eluded him. “The disease simply had its way”, Newman concluded. “It came like a thief in the night and stole treasure.”of

Like other historical events that inspire great anxiety, pandemics, argues Winter, move many us to draw a veil over them. Remembering is hard; far easier to forget.

But if pandemics end when we begin to forget about them, bubbling under the surface there is also a countervailing psychological imperative: namely, the need to remember so as to “learn the lessons” and avoid making the same mistakes again. That is the imperative driving calls from bereaved families for an independent judge-led public inquiry into the UK government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic.

Towards a new politics of memory

At the heart of these demands, I would argue, is an urgent moral story, one with plenty of agency. For instance, it is a story that would examine why, despite the former Health Secretary Matt Hancock’s promise to throw a “protective ring” around the elderly, UK care homes registered in excess of 66,000 deaths between March and June 2020. And it would examine why Britain was so slow to order personal protective equipment for doctors and other frontline health workers, such as Dr Abdul Mabud Chowdhury, a 53-year-old consultant urologist who died of Covid in April 2020 shortly after an issuing an appeal to the government for “appropriate PPE”. And it would ask why at a time when millions of Britons were under lockdown restrictions, the Prime Minister and his acolytes held a succession of parties and social gatherings at No 10 Downing Street in an apparent breach of the lockdown regulations.

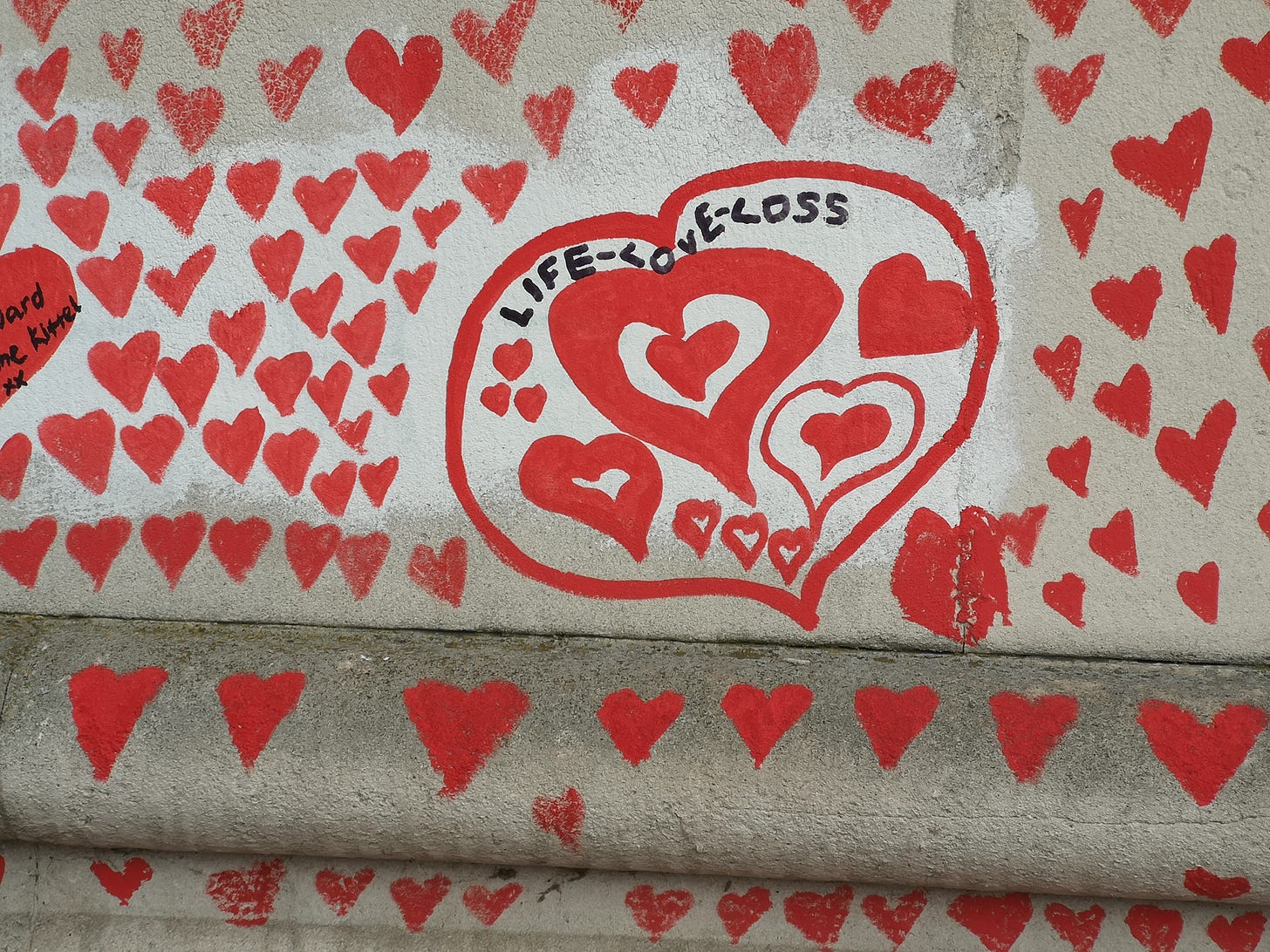

Unlike previous pandemics, when quarantines and lockdowns made it hard for people to share news of deaths and their collective experiences of bereavement, Covid-19 has seen a surge in digital connections enabled by Zoom and other social media platforms. The result is that even as the government has been calling for us to draw a line under the coronavirus pandemic, groups like Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice have been urging their members to share their memories on Facebook and Twitter – or make a pilgrimage to the National Covid Memorial Wall on Albert Embankment, an unauthorised “people’s memorial” emblazoned with 150,000 hand-drawn pink hearts, one for every British victim of Covid-19.

Already, the wall – and its digital correlates – are engendering a new politics of memory, one in which activists, with the support of religious and moral leaders, are increasingly able to dictate what form memorials to the coronavirus pandemic should take, and whose memories should be accorded prominence. Even establishment institutions, such as the Anglican church, are having to adapt their rituals and traditions to the digital age: hence St Paul’s Cathedral’s Remember Me project - an online book of remembrance supported by the Dorfman Foundation and Microsoft, among others.

On 10 March, many of these activists and representatives of the bereaved will join memory studies scholars and medical historians for a discussion on “Connecting in the time of Covid” at the Department of Journalism at City, University of London.

For those of us invested in this project, there can be no ending to the pandemic as long as questions about responsibility for the death toll remain un-answered, and as long as the coronavirus continues to claim new victims. Nor will the grief for those who are gone dissipate simply because the government says it’s time to put Covid behind us.

The workshop “Connecting in the time of Covid”, will be held at the Department of Journalism at City, University of London, on Thursday, 10 March, 2022. To see further details of the event and for free registration, click here.