Corona roulette

The current wave of corona infections is shaping up to be as bad as anything we experienced during the lockdowns. Welcome to the Spring of "living Covidly".

This was the year that things were supposed to return to “normal”, when we would stop worrying about the coronavirus and start treating it like flu.

“Do go to work if you have a headache or feel tired”, announced the Daily Mail on Wednesday paraphrasing the latest advice from the UK’s health secretary Sajid Javid. “If I was feeling a bit tired, I’d reach first for the Nurofen,” he added unhelpfully.

Just to make sure the British public got the message, the very same week the British government ended free Covid testing, leaving those worried about infecting their families or co-workers to play corona roulette.

Meanwhile, my phone has been ringing off the hook with inquiries from friends shocked to discover that there’s been a run on lateral flow kits and do I perhaps have one they could “borrow” (my current rate is £20 per kit - sometimes it pays to be a pandemic specialist).

To compound the Spring corona madness, the previous week nearly five million Brits tested positive for Covid – the highest number ever recorded by the Office of National Statistics. Meanwhile, there are currently 20,409 patients in hospital, more than at the peak of the Omicron wave in January. And although only 361 are on ventilators, the NHS’s ability to cope has been severely compromised by staff shortages due to the numbers of nurses and doctors having to isolate with… you guessed it, Covid.

The result is a crisis that is shaping up to be every bit as bad as the one that triggered the UK’s first two national lockdowns, with many hospitals warning patients to stay away except in “genuine, life-threatening situations”.

From my perspective, the most intriguing aspect of the latest wave of infections is the silence with which it has been greeted by Covid sceptics who were so quick to criticise the earlier lockdowns on the basis that they might do more harm than good.

Well, to see what the pandemic might have looked like in the absence of lockdowns or, indeed, any other kind of restriction (since February Britain, has no longer required people to wear masks on trains, buses or in other confined spaces) you only have to look at the government’s present “living with Covid” strategy.

In London, the more infectious BA. 2 version of Omicron has taken out whole teams of executives, with “offices emptying fast”, according to the Financial Times. And in those industries where employees cannot afford to take time off work the official government advice has only exacerbated the situation as “mildly” infected individuals who show up to the office are spreading the disease to healthy colleagues. The result is that one in seven UK firms are unable to trade normally.

And this, remember, is with Covid vaccines and booster programmes, something that didn’t exist two years ago.

How much worse might staff absences have been and how much greater the pressure on the NHS – and how many more people might have died - had the UK not imposed strict lockdowns, thereby buying time for the development of vaccines and therapeutic drugs?

That is not to say that lockdowns were not without harms: there is growing evidence that infants and young children were severely impacted by the repeated nursery and school closures, with child development specialists reporting some children mimicking the voices of characters in movies and TV programmes due to too many hours spent in front of screens. Just as worrying is the recent Offsted finding that many children whose development coincided with the adoption of face masks by adults and siblings lack the ability to read facial expressions and also lag behind on other social skills.

But none of this should not detract from the criticism of the government’s current strategy. At the university where I teach, seminar plans have had to be hurriedly rewritten and assessements delayed due to the numbers of students absent with Covid or symptoms resembling it (after all, in the absence of tests, who can tell?).

And forget about going on holiday. You may no longer need to pay for pre-flight tests but at Manchester airport holidaymakers are having to queue for 90 minutes just to reach a check-in desk, while those seeking to fly from Heathrow have been told to arrive three hours early to be sure of clearing security in time. The cause? A shortage of check-in staff and baggage handlers because of record unfilled vacancies and staff absences due to Omicron.

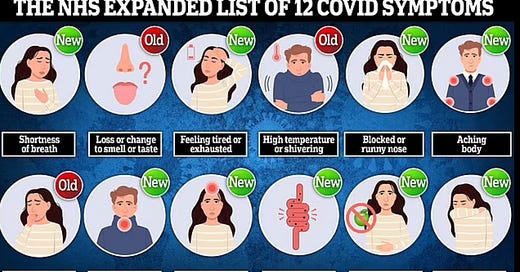

The irony is that all this coincides with the NHS’s long-overdue decision to expand the list of Covid symptoms. Whereas previously the NHS only recognised a high temperature, a cough and a loss or change to taste or smell as symptoms of Covid, it has now expanded the list to twelve, including a headache, a sore throat, a blocked or runny nose, and body aches.

The revised list will come as no surprise to those who were denied admission to hospitals earlier in the pandemic because their symptoms were considered “mild” or who developed long Covid only to discover that GPs were unwilling to take their condition seriously. Perhaps that explains why last October a 27-year-old with a promising career ahead of him as a health consultant at McKinsey was found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning in his car in Hertfordshire.

Abhijeet Tavare had won dozens of scholarships and prizes for academic and sporting achievements while studying medicine at Oxford but had become depressed after developing long Covid in September 2020. Though Tavare consulted five doctors and therapists, none of the treatments on offer made a difference to his symptoms of brain fog and fatigue and in a suicide note written shortly before his death Tavare explained that he “didn’t want to suffer any more”.

He is not alone. The latest ONS figures suggest that as many as 1.7 million Brits, or three percent of the population, may be suffering from long-Covid and that 281,000 are so ill they struggle to complete simple day-to-day tasks. These statistics should alarm employers – or indeed anyone concerned about productivity and the long-term performance of the British economy. Yet to date the government has invested just £50 million in research into this debiliating condition.

Regular readers of this Substack will know that the symptoms of long Covid are eerily similar to the peculiar fatigue states observed after the 1889-93 “Russian influenza” pandemic. These fatigue states and “psychoses” coincided with a marked increase in suicides, with the suicide rate in 1893, the third year of the pandemic, peaking at 85 per million, the highest on record. A similar pattern was observed in Paris and other European capitals coincident with the pandemic.

As I noted in a recent post, some scientists suspect the Russian influenza may be a misnomer and that the pandemic may have been due to a coronavirus, albeit one that originated in cows rather than bats, which are the most likely source of Covid-19.

Unlike the 1918-1919 Spanish influenza, which we know was caused by an H1N1 flu virus, and which fizzled out in around 1920, the Russian influenza never really went away but continued to cause sharp spikes in morbidity and mortality throughout the 1890s.

If that is the case, this year may only be the beginning. Gird yourself for what could be a decade of living Covidly.